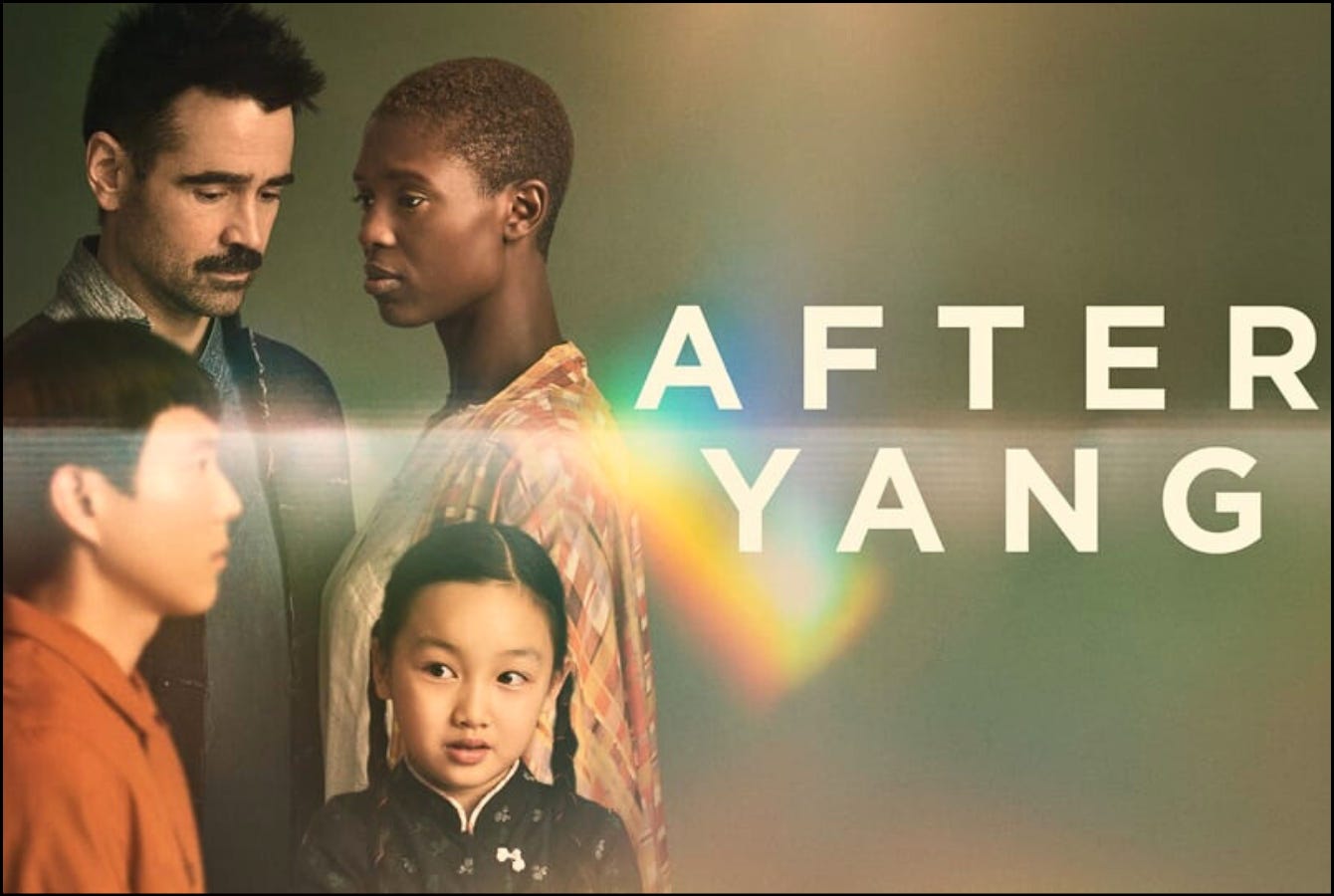

"After Yang": Human and Humane

How Kogonada's "After Yang" uses the artificial to explore — and celebrate — what it is to be human.

After Yang, Screenplay & dir. Kogonada (2021)

As a critic, I sometimes have to work against the distancing effect that the analytical mind brings into the cinema. Usually, film analysis blends seamlessly into the viewing experience, but it can sometimes be a hindrance. I occasionally find myself distracted from the film by mentally reworking an opening sentence of the inevitable review, or trying to remember if the shot in front of me is called a Dutch angle or an oblique something. And then there are those films that sneak up on you, sliding past your higher cognitive faculties, to hit you right in the heart and sweep you away in their narrative flow. The opening moments of After Yang filled me with so much joy that I was instantly sucked into its world.

The sci-fi trappings of that world are remarkably easy to articulate and, for the first-time viewer, easy to understand. In the near-future, lifelike androids are sold to families as “siblings” designed to educate children. Jake and Kyra, having adopted Mika from China, are eager for her to learn about where she comes from. Their anxiety is understandable given one of the film’s many lovely (and understated) details – the name they’ve given her, “Mika”, is actually a Japanese name.

Yang is an artificially intelligent android that (who?) has been purchased to provide Mika with both company and “Chinese fun facts”, as if a steady stream of data points might eventually answer her fundamental question: what makes a person Asian? This question fits within a branching tree of existential searching, being one node away from the question of what makes a family, and what specifically makes her part of her adoptive family. All of these questions fall within the broader, grander question of what makes one human.

I don’t want to give away too much here – After Yang is a compact film that stuffs a lot of big ideas into its short runtime – but I have to gesture at the fact that mortality plays a large role in the answer to that last question. Endings are vital to a sense of meaning. At one point, Yang teaches Kyra a proverb from Lao Tzu: “What the caterpillar calls the end, the rest of the world calls a butterfly.” It’s telling that the film begins with Yang suffering what might be a terminal breakdown, and that the story proper is told primarily in flashbacks. After Yang is a study of the idea that, as Kierkegaard reminds us, life must be lived forwards and understood backwards.

That asynchronous directionality for living and understanding life is further scrutinised in Kogonada’s screenplay and through his direction. In the first shot of the film, Jake, Kyra, and Mika are posing for a photograph, waiting for Yang to set up the camera and join them in the frame. The camera clicks and whirrs and – here is the second shot of the film – the image suddenly flips over and back again, as if replicating the camera’s internal process. The magic of what After Yang is doing, amid all of its sci-fi speculation and mystery-teasing, is contained in this simple visual idea: in the act of recording memories, we alter them.

We know from various strands of research that two basic things are true of memories. First, that we retain them only by going over them again and again. Several studies show that one of the many reasons sleep is so vital is that the unconscious mind reviews memories and transcribes them from short- to long-term storage. When it comes to memory, it really is true that if you don’t use it, you lose it. The second fact is that each time we revisit a memory, we subtly alter it, magnifying or diminishing certain elements, incorporating new information, even absorbing into our own memories other people’s memories. (For many years, I believed I’d seen a bird run over by a car when I was little, a memory that turned out to be false – my brother had seen it and his repeated account was so evocative that my child’s mind had latched onto it as its own.) Like the observer effect in physics, our memories are shaped and reshaped every time we look at them.

Kogonada employs a deceptively simple and devastatingly poignant method of evoking this shifting, rewriting nature of memory. In his flashback sequences, we frequently glimpse alternative takes in which a shot is subtly shifted or a facial reaction altered. Most notably, there are many alternative line readings: we hear the character say a line in voice over, as if practicing it, and then watch them deliver that same line with a slight change in its inflection or tone. What this shows us is the reality that when it comes to memory, there is no “fact of the matter”. We are always attempting to replicate the truth of what happened, but that truth is so much deeper than literal transcription can express.

The most captivating scene, for me, is one in which Jake tries to teach Yang about what he loves about tea. There’s so much to parse and to love about what happens here – and about what is said and unsaid – but I’ll leave you with Yang (who, recall, is not a human) expressing regret about his inability to feel what Jake feels. “I wish Chinese tea wasn’t just about facts for me,” he says. “I wish I felt something deeper about tea.” This is the truth of Yang’s artificial intelligence: that it may be able to record the facts of a memory better than the human mind, but it cannot grasp what’s beneath those facts. After Yang suggests that what makes us human – to borrow the words from Jake, as he fails to articulate why he loves tea – is something we haven’t the words for.

After Yang isn’t a perfect film, but it’s wonderful, which is so much better than perfect. It also isn’t particularly interested in the workings of its material world, so it won’t satisfy die-hard fans of hard sci-fi. Thankfully – for those of us left cold by hyperdrives and trade agreements between galactic federations – After Yang is far more interested in humans and the humane.