It seems to me that the mantra by which some Christians dismiss tough questions about God — that he “works in mysterious ways” — says less about the nature of the Divine and more about our own human limitations. His ways, presumably, are not a mystery to him but to his followers, and, as Wittgenstein once wrote, “That whereof we cannot speak we must consign to silence”. Religion is by no means the only house in which unknowability lurks in the basement. As Roger Scruton writes in his wonderful essay Effing the Ineffable:

“Every enquiry into first principles, original causes and fundamental laws, will at some stage come up against an unanswerable question: what makes those first principles true or those fundamental laws valid?”

The answer, he suggests, always comes back to this:

“And the answer is that there is no answer — or no answer that can be expressed in terms of the science for which those laws, principles and causes are bedrock. And yet we want an answer. So how should we proceed?”

How should we proceed? For that matter, where should we begin? Let’s begin with another question, one for which I have yet to give a satisfactory answer: why have I started going to church?

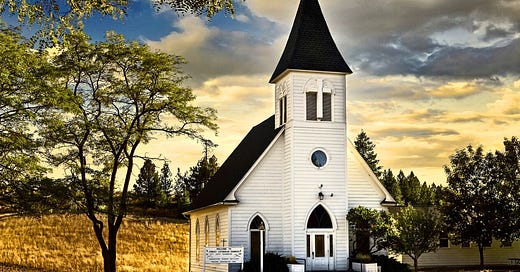

Every Sunday, I get myself dressed, roll my begrudging wife out of bed (though she’s always grateful once we’re out the door), and we go along to a nearby service. The building isn’t one of those ancient parish churches written about in tender yet wary terms by Philip Larkin in Church Going. There is no “small neat organ”, but a band with crashing drums and huge energy. There are no esoteric “parchment, plate and pyx in locked cases”; instead there are jeans and tee-shirts, tambourines and banners, the near-constant sound of children echoing through what otherwise would be “unignorable silence”. In one key way, however, this church is just like Larkin’s, and like every other church I’ve stepped into — it is “a serious house on serious earth”.

And what, my curious friends want to know, brings me to that church? There’s a ready-made answer that would satisfy most of the people who ask. I could say I go to church because I believe in God. That would instantly suffice, even if the next question would then be about why I believe in God. Belief — in the somewhat reductive manner belief is thought about in our unbelieving age — makes sense of going to church. The problem with that answer is that I don’t believe in God. At least, not in any manner and not in any god that others would recognise as “believing” or “God”. The closest that language can get me here is to say that it’s complicated, which is the secular cousin of “God moves in mysterious ways”.

Not being able to give the Christian’s answer to why I go to church, I stumble over half-answers and partial explanations, none of which satisfy the asker and all of which diminish complexity with language that isn’t up to the task. It’s the language that I blame for the problem. It turns out that the modern vocabulary is ill-equipped to discuss the heady things that church inspires. I want to talk about spirituality, mystery, even the Divine, but spirituality in the modern age is little more than star signs and psychics, and mystery is something that science will one day solve. Worst of all, the Divine has been stripped of its definite article and capitalisation to become a piece of hyperbole that means something is really, really good. And it’s a brand of chocolate.

The dissolution of our cultural lingua franca was made evident with the recent news that Tate & Lyle are changing their iconic logo. The branding used to depict a dead lion swarmed by bees, above the phrase, “Out of the strong came forth sweetness”. This is, of course, a reference to the Biblical story of Samson, and many have been quick to assume the rebranding is intended to eliminate religious overtones. This has been encouraged by journalists sharing a quote from one professor of marketing (with no known link to Tate & Lyle) talking about religious belief putting the brand “in an exclusionary space”.

Regardless of the company’s motivation for the rebrand, what’s telling is how every single article about the tweetstorm in a teacup explains to its readers the story of Samson and its link to golden syrup. While the image would have once been self-explanatory to a Biblically literate public, today it’s a dead language to most. We can no longer assume we’ll be understood when we use Biblical allusions. Good luck, then, telling someone of this new cultural context that you go to church because of the deep profundity of liturgy, or the wellspring of meaning that is Scripture. Agape, Eucharist, Logos: it’s quite literally all Greek to them.

If the person I’m talking to seems truly interested and not in a rush, I’ll give them what I believe to be the fundamental reason beneath myriad contingent reasons for my going to church. I tell them that I’m simultaneously searching for philosophical bedrock and the highest value that transcendence points to. I’m convinced that by finding one I’ll find the other, that these two poles — which the poet E. E. Cummings describes as “the root of the root” and “the sky of the sky” — lead to each other in one of Douglas Hofstadter’s strange loops. It’s usually at the strange loops where I lose them.

When I speak of philosophical bedrock, I’m thinking of something like Scruton’s “unanswerable question” at the bottom of our searching. This is the rock on which a worldview and a life can be built, as opposed to the shifting sands of relativistic cultural norms. Of course, not all metaphysical presuppositions are created equal. Some lead to the aesthetic and moral wisdom of Marilynne Robinson, or the courage of Martin Luther King, Jr; others lead to the intellectual cul-de-sac of Young Earth Creationism, or the ethical nihilism of believing gay people should and will burn in Hell. I’m looking for somewhere to place my faith so that the life I build on it will be as free as possible from such moral and intellectual failings.

As for “the highest value”, what I really mean by that is a master value, a thing that sits above all else. Transcendence as I understand it — borrowing broadly from a conversation between Roger Scruton and Jordan Peterson — is our best intimation of something beyond ourselves, beyond our objective knowledge and subjective experience, something that we are always reaching towards. Some call this highest value God, others call it the Divine. I’m still searching for the language to help me grasp my way, however imperfectly and falteringly, towards whatever it might be.

This is why I go to church: because religion has a language with which I can articulate my questions. Christianity in particular is equipped with a vocabulary that can speak of the deepest things, of sin, of redemption, of the numinous, of the sacred and the profane. It’s an expansive language that can encompass so much with so few words. All of my efforts to bear the burden of living, to hold myself up in the face of trauma, to struggle with the moral dimension of life and to do it with joy in my heart, happy for the opportunity to help other souls make it through the hardest times: all of this is contained in Jesus saying, “Take up your cross and follow me.”

Or take one of the central lessons of the opening verses in Genesis. Order is created from chaos, and it’s good. This is at the beginning of all things, not only our universe, but of all our endeavours. If we’re designing any kind of order, be it moral, aesthetic, or otherwise, to make sense of the chaos around, we are doing good. How does God achieve this in Genesis? “And God said...” Language. And how does God repeatedly reveal the nature of Divinity to humans throughout the Bible? By his various names — more language. There’s a reason that Muslims describe Jews and Christians as “People of the Book”, defined and guided as they are by the Bible. Language plays an interesting and vital role in the religion that claims “the Word” is both with God and is God.

Language has its limits, of course. For a start, many of the Christians I share that sacred space with on a Sunday have very different definitions of some core words. “God” means something very different to them than it means to me. I don’t believe in the supernatural, which in my view doesn’t rule out some kind of creative force or first mover, but it does create friction around things like virgin births and resurrection. I’m sure that if I were to lay out what I mean by words like “God”, or “Hell”, or “Holiness”, many of my fellow church-goers would see my views as quite heretical. But at least they use the words, and at least we are able to have that conversation. I find myself needing to engage with people who take those words seriously even if they use them differently.

Then there’s the fact that experience precedes language. All our fine words signify something that exists independently of them, which means that there is a fact of the matter that has some quality that cannot be experienced through the secondary nature of the words that describe it. Just as Christians believe that God existed before we had the word God, it seems to me that there is some experience to be had before words can be made useful. In spite of my chasing after language, I can’t talk my way to a meeting with the Divine. Instead, language is how I sculpt my understanding of a deeper, more profound reality. In fact, that reality is described with great lucidity by the writer

. In an essay on his Substack, he wrote:“What if a human being is not primarily a rational, bestial or sexual animal but in fact a religious one? By ‘religious’ I mean inclined to worship; attuned to the great mystery of being; convinced that material reality is only a visible shard of the whole; able across all times and cultures and places to experience or intuit some creative, magisterial power beyond our own small selves.”

If I had not experienced the fact of this religiosity — had I not felt in my bones the human yearning for something higher than ourselves, the conviction that we live in the midst of things beyond what we can know, the intuition not only of order but of the goodness of that order — then Kingsnorth’s words likely would have fallen flat at my feet. Instead, they made something in my soul (another fiercely contestable piece of language) vibrate, like the hammer that strikes a bell. Then I set out to describe that sound in language. A word is no more the thing itself than Rodin’s The Kiss is a literal embrace between real-life lovers; but just as Rodin’s sculpture points us towards true intimacy, words can guide us towards understanding.

Like Jacob wrestling with God, I continue to struggle with language. As I do, I’m aware of some deep, slowly dawning truth that glows like a distant yet discernible light at the furthest end of the deepest tunnel. It’s the truth that, at some point, words will ultimately fail. Language will have no purchase on the things that matter most, that which is at the highest of highs and at the bottom of it all. I haven’t yet reached that place, though I suspect I will, just as I suspect that coming to that place sits at the centre of all meetings with the Divine. It is, I hope, waiting for me there in the road ahead. If I ever reach it, language will likely do no better than to describe it as a peace that passes all understanding — words borrowed, again, from the Bible.

Further reading:

• Effing the Ineffable, Roger Scruton (2010)

• Church Going, Philip Larkin (1954)

• [i carry your heart with me(i carry it in)], E. E. Cummings (1952)

• “Atheists in Space”, in The Abbey of Misrule [Substack], Paul Kingsnorth (2023)