"Cat's Cradle": Man Cannot Live on Truth Alone

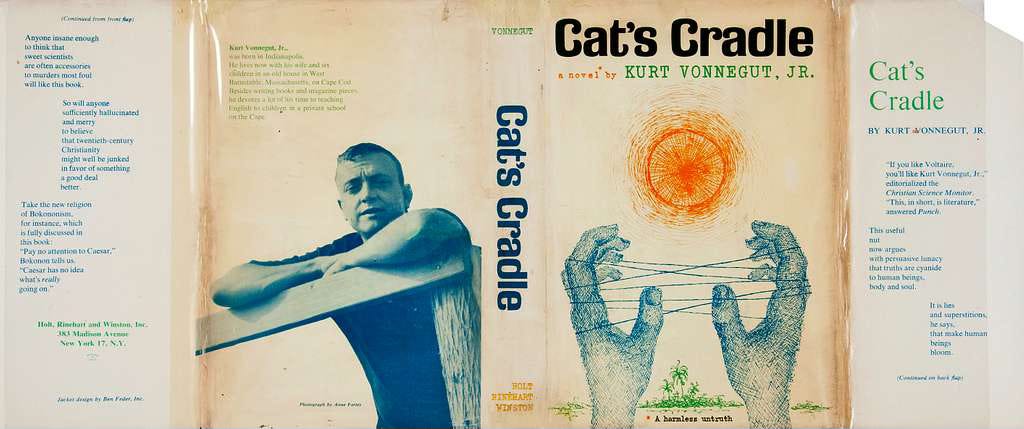

On Kurt Vonnegut's "Cat's Cradle" and a reckoning with the twentieth century.

Kurt Vonnegut was a man of mixed signals — or, more charitably, a man of Whitman’s contradictory multitudes. He was a self-declared humanist who once wrote, “Evolution can go to hell as far as I am concerned. What a mistake we are.” He also described himself as a “Christ-loving atheist”, and in spite of his rejection of formalised religion, he once gave a sermon on Palm Sunday at an Episcopal church. In that sermon, Vonnegut said:

“Laughter and tears are both responses to frustration and exhaustion, to the futility of thinking and striving anymore. I myself prefer to laugh, since there is less cleaning up to do afterward — and since I can start thinking and striving again that much sooner.”

It was this instinct towards humour in the face of tragedy, as well as his ability to keep two sets of books, that defined Vonnegut as a writer. He certainly knew a thing or two about tragedy: he’d been a prisoner of war in World War II; he discovered his mother’s suicide at home on Mother’s Day; he suffered major depression throughout his life. His response to these horrors was distilled in that famous verbal shrug from Billy Pilgrim in Slaughterhouse Five: “So it goes.”

For Vonnegut, irony was a blade with which he cut through the existential absurdities of life. His use of irony was both defensive (distancing him from his subject) and offensive (having placed himself at a reach, he had room to swing his sword). In Slaughterhouse Five, his target was war itself. In Cat’s Cradle, he’s more specific but no less grand in his ambitions, making the subject of his scornful pen the legacy of the atomic bomb.

Here, Vonnegut offers us the character of Dr Felix Hoenikker, a founding father of the bomb and literal father to three unusual children. Dr Hoenikker remains a distant paternal figure, never “present” in the novel but remembered by others at a distance. These memories are given to the book’s narrator, a writer named Jonah. He’s actually named John, but he prefers Jonah because — like the Biblical figure sent by God to warn Nineveh against their wicked ways — “somebody or something has compelled me to be certain places at certain times”.

Jonah discovers a religion called Bokononism that has a term for precisely this kind of narrative intervention: zah-mah-ki-bo, which means something like “inevitable destiny”. Fate will conspire to have Jonah meet Dr Hoenikker’s three children on an island nation, along with the island’s dictator, a teenaged goddess, and a former Auschwitz physician. It’s that kind of book. Full of satire, wordplay, truncated chapters, and cosmic consequences played out among the rabble of humanity, Cat’s Cradle is among the very best of Vonnegut’s novels.

But is Cat’s Cradle a novel? Vonnegut’s books are often made up of snapshots laced together with narrative floss, liable to snap if pulled too hard. In Cat’s Cradle, the accumulation of events is reminiscent of a plot, but the heavy use of coincidence flies in the face of what we typically think of as good storytelling. Cat’s Cradle, then, is more like an extended parable. Rather than questioning the world, Vonnegut is attempting to represent it — if not accurately then at least honestly.

Forget also about anything like a character arc. These people are who they are, and they stay who they are throughout the story. Jonah becomes a Bokononist, sure, but that merely gives him a new vocabulary with which to express the man he’s always been. The characters here are not intended to provoke questions or interrogate the nuances of the human condition; they serve to make a point. This is most clear in the character of Dr Felix Hoenikker.

Dr Hoenikker stands in for the anti-human indifference of what we might call “scientism”. First, he (like his science) is incapable of reaching people where they live. There’s a wonderfully dry exchange between Jonah, a prostitute, and a bartender, in which they talk about having read somewhere that scientists had discovered “the basic secret of life”. They aren’t terribly excited by the answer. “Protein,” the bartender says. “They found out something about protein.” The mood here is like a collective shrug: what does protein have to do with their real lives?

Dr Hoenikker would no doubt tell them it’s important — perhaps supremely important — because it’s true in the scientific sense. He once told an assistant that all he cared about was truth. But the assistant says, “I just have trouble understanding how truth, all by itself, could be enough for a person.” It can’t be, as is painfully learned by anyone who’s outgrown that phase of nascent maturity in which materialism replaces the unconsidered superstitions of one’s youth.

This simplistic belief in the singular importance of truth — at the expense of poetry, emotion, narrative, and fellow feeling — can be dangerous. Cat’s Cradle exists in the afterglow of the atom bomb, in the lingering smoke of the ovens at Auschwitz, built by scientists and engineers who’d reduced people to a calculation with a (final) solution. Here, Dr Hoenikker invents “ice nine”, which can instantly freeze Earth’s water, simply as an intellectual lark. He’s the epitome of those scientists warned about in Jurassic Park, so preoccupied with whether he could, he didn’t stop to think if he should.

But the stakes don’t have to be on the scale of extinction to matter: the damage of scientism can be personal, though no less devastating. The three Hoenikker children are so alienated from their cold, unfeeling father that the only time he smiled at one of them, it scared them so much they burst into tears. While reading Cat’s Cradle, I was reminded of a recent conversation between Richard Dawkins and Christian-convert Ayaan Hirsi Ali.

Ali told the story of how religion had saved her from alcohol abuse and suicidal nihilism, filling the aching void she felt in her soul with hope and faith. Dawkins looked blankly at her and could only ask if she literally believed that Jesus was born of a virgin. He couldn’t see past the facts to witness her humanity. We’re right to see that truth has a place in what matters most to us; we’re wrong to insist that truth is what matters most. And we deny our own humanity when we believe that matter is all that matters.

Dr Hoenikker is a cautionary figure, meant to portray in the negative what Vonnegut meant when, in a speech to the American Physical Society, he described a “humanist physicist”.

“What does a humanistic physicist do? Why, he watches people, listens to them, thinks about them, wishes them and their planet well. He wouldn’t knowingly hurt people. He wouldn’t knowingly help politicians or soldiers hurt people. If he comes across a technique that would obviously hurt people, he keeps it to himself.”

A humanist physicist is one who’s married their head and their heart, who balances science with values. It’s a scientist who sees that scientific truth, all by itself, is not enough for a person.

In Cat’s Cradle, Jonah looks back on recent history in an effort to make sense of it. This has been the preoccupation of Western civilisation since the second half of the twentieth century. Conservative writer Douglas Murray has described our present moment as “a footnote to the twentieth century” in which “we’re still trying to work out ‘what happened’.” Future historians, Murray says, will look back on this era as the “post-Holocaust, post-World-War-II, post-gulag world”. No doubt Cat’s Cradle will take a place in the documents useful to such historians — and it’s equally important for us today.

These accounts of twentieth century horror can act as a firewall against the same impulses that led to it. There’s a moment in Cat’s Cradle where Jonah recounts the tenant living in his apartment while he was away on his writing assignment. The tenant was “a poor poet named Sherman Krebbs”. When Jonah returned to the apartment, Krebbs was gone, and the place had been “wrecked by a nihilistic debauch”:

“He had run up three-hundred-dollars’ worth of long-distance calls, set my couch on fire in five places, killed my cat and my avocado tree, and torn the door off my medicine cabinet.”

Jonah had recently received what he took to be a cosmic symbol of significance, one that he says here he might have been inclined to dismiss as meaningless, “and to go from there to the meaninglessness of all”. An observer of our species in the aftermath of the Holocaust, the gulags, and the atom bomb might reasonably extrapolate meaninglessness from those manifestations of soulless nihilism. But in many cases, what actually happens is the reverse, as is the case for Jonah:

“But after I saw what Krebbs had done, in particular what he had done to my sweet cat, nihilism was not for me.”

In writing his novels, Vonnegut rejected the nihilism that he might have adopted after all the tragedies he’d witnessed. He turned suffering into art. Here, then, is one more example of the contradiction, complexity, and paradox that define Vonnegut’s writing: even in its pessimism and occasional cynicism, Cat’s Cradle is a work of hope.

I found your blog around a month ago and have since gone down the rabbit hole of your writing. Every essay is written in a way that draws me in, even if I have never had interest in the subject of the piece. Please keep writing, your work really makes me stop and think about what I've read in a way that few substack pages do :)