"Ex Machina": Through the Looking Glass

On the 10th anniversary of "Ex Machina", we take a look at its masterful exploitation of empathy, and what the film says about our capacity to feel another's feelings.

Ex Machina, dir. & screenplay Alex Garland (2014)

The psychologist Paul Bloom is against empathy. He’s not opposed to compassion, and he certainly has nothing against caring for others. In fact, his antagonism towards empathy largely rests on the accusation that in moral decision making, empathic responses — rather than cold-blooded rationality — often lead to unfair outcomes for others.

In his book Against Empathy (2016), Bloom doesn’t impugn the ability to understand another person’s experience, variously called theory of mind or social intelligence. Instead, he criticises the proclivity for feeling what another person is feeling. “If you feel bad for someone who is bored, that’s sympathy,” Bloom writes, “but if you feel bored, that’s empathy.” He goes on to describe ways in which empathy leads to poor ethical choices.

Take, for instance, sentencing in criminal trials. A lenient or a harsh sentence might depend on whether the judge can be made to empathise with the victim or defendant. The victim might be articulate or mumbling; the accused could be flamboyant or unflaggingly stoic; one might be a widow just like the judge, or share the skin colour of the majority of a jury. Any of these extraneous details could move a judgement, which is why justice based on empathy isn’t impartial — it’s no justice at all.

Yet empathy is our doorway into Alex Garland’s sci-fi brainteaser, Ex Machina. We enter the film through the eyes of Caleb, an apparently lucky (if somewhat bland) tech employee who’s won a visit to the mountain home of his CEO, the far more glamourous Nathan Bateman. We wonder along with Caleb what Nathan will be like, what might happen on this week-long retreat, what Caleb will be expected to do, and this empathy breaks down the division between character and viewer.

Hergé used this device with Tintin, his blank-slate protagonist with no backstory to prevent the reader’s intimate identification with the boy reporter, so we slip right into his adventure. The manipulation of our empathy in Ex Machinaserves to signal that Caleb is our protagonist. He’s the first person we meet in the movie; we follow his journey to the secluded house-cum-laboratory; he’s as unfamiliar with Nathan as we are. His story seems to be ours. Ex Machina then spends the rest of the movie challenging this assumption.

Nathan has built an automaton named Ava that (who?) has artificial intelligence. Caleb must engage in an extended Turing Test to determine if Ava is conscious. As you’d expect of an Alex Garland script, this isn’t the full story. Eventually, Nathan reveals that the experiment is actually designed to learn if Ava can make Caleb forget that she’s not human. Can Ava manipulate his empathy so she can escape?

After his first interview with Ava, Caleb is amazed, saying:

“When you’re talking to her, you’re just ... through the looking glass.”

You’ve got to love a well-placed hint at subtext. Ava is Lewis Carroll’s Alice, in a wonderland where the rules must be learned to escape from Nathan’s compound. Like Alice, who begins as a pawn and crosses the chessboard to be made a queen, Ava begins as Nathan’s puppet and must navigate the ontological terrain of his game to convince Caleb to make her his “queen”. To do so, Nathan says, she’ll “have to use imagination, sexuality, self-awareness, empathy...”

Empathy is one of the tools with which (Nathan assumes) Ava will win Caleb over, but it’s not quite empathy in the usual manner. Ava doesn’t need to actually feel Caleb’s feelings to trick him into helping her escape. Empathy of that kind would probably put her off exploiting Caleb’s affections. Stimulating Caleb’s empathy, on the other hand, is a vital component to convincing him to act in her favour.

This is one way that Ex Machina upends our received thinking about empathy. It’s easy to think that the other person’s experience is an objective thing that “exists” out there in reality, while our vicarious, empathic experience is an illusion. The person who smashes their thumb with the hammer actually feels the hot ache that invokes the torrent of curse words, but our own flinch and gasp are caused by merely imagining how it felt. However, there are instances where empathy is an act of projection onto the other person.

Caleb supposes that he knows what Ava feels and, if asked, he might tell us he’s empathising with her, reading her internal world and reimagining it for himself. But her manipulation of his emotional state is, in fact, deliberately causing him to ascribe to her emotions that begin in him. He’s like a child who believes a rock with a smiley face drawn on it feels happy. Here, Caleb sees a sultry look pass over Ava’s face and assumes it accurately reflects something she feels within, that she fancies him.

In reality, Caleb feels lust for her, and he desires that she feel it too, so he adds those emotions to his theory of her mind. Empathy becomes a form of self-deception, masking emotional projection as emotional mirroring.

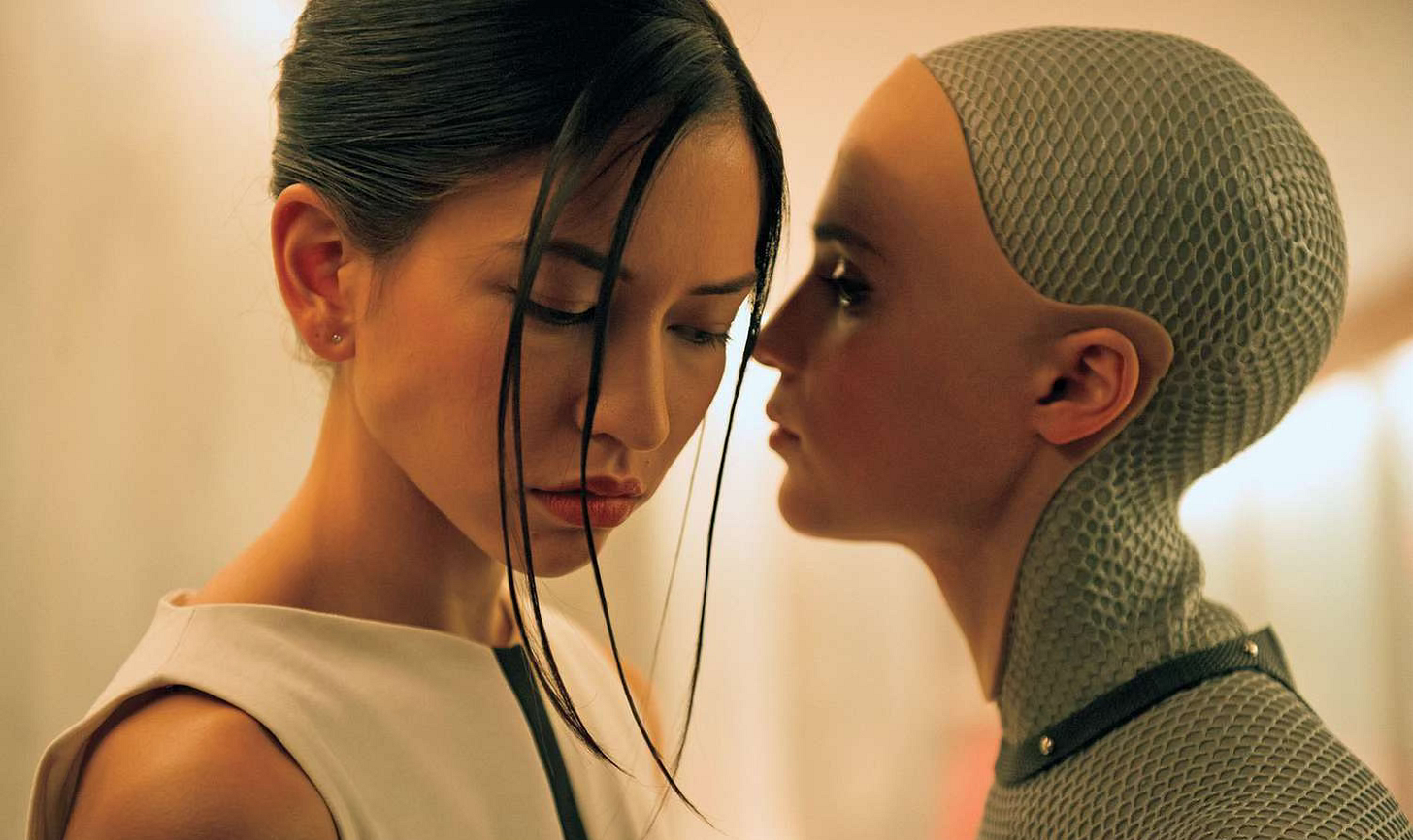

The visual allusions to Ava’s journey through the looking glass are everywhere: in split-shots and reflections, intimating the layers of duality running through Ex Machina — in Nathan’s experiments, Caleb’s scheming, Ava’s nature, and in the development and utilisation of empathy. These mirror images underscore the moral gymnastics that inform the second act of the story. One of the most prominent “reflection shots” comes at the end of the film.

Just as Alice doesn’t remain a queen in Wonderland, Ava doesn’t remain Caleb’s queen. Having “won” the existential chess game of Nathan’s experiment, she stabs her maker, locks Caleb inside the house, and makes her way into the real world. The closing shot shows Ava’s reflection in a store window, her translucent form taking in the world around her before vanishing into a crowd. We might consider the fact that the last time we see her is in a reflection — a representation of duality. This is an appropriate end to a movie that’s consistently split audiences in their interpretations of it.

Garland revealed to Den of Geek in 2020 that he’s always viewed Ava as the protagonist. “People made a set of assumptions about Ava,” he said, “that she was just a cold, bad robot doing cold, bad things, as opposed to empathising with her as a sentient being who’s being treated unreasonably.” He added:

“I’ve never liked the interpretation that [Ava] has no empathy ... She may well have empathy for the other robot. And that robot might have empathy for her. Just because something doesn’t have empathy for you doesn’t mean that they’re incapable of empathy.”

An important part of Ex Machina’s ending is that, over the course of the movie, we’re made to empathise with Ava, so her eventual betrayal of Caleb feels like a betrayal against us too — meaning also that the object of our empathy suddenly and somewhat confusingly switches to Caleb in the finale. With our loyalties wrenched from one side to another like this, our empathy is exposed as a poor guide to anything objective.

Let’s assume that Ava feels real empathy towards Nathan’s other robot. You might think that if Ava felt empathy for Caleb instead, she wouldn’t have made the ethically dubious decision to lock Caleb inside the house. But how would you convince Ava to move her empathy from the robot to Caleb? Any sensible attempt to do so would appeal to reason and logic, which reminds me of a study cited by Paul Bloom in his book:

“[They] told subjects about a ten-year-old girl ... who had a fatal disease and was waiting in line for treatment that would relieve her pain. Subjects were told that they could move her to the front of the line. When simply asked what to do, they acknowledged that she had to wait because other more needy children were ahead of her.

But if they were first asked to imagine what she felt, they tended to choose to move her up, putting her ahead of children who were presumably more deserving. Here empathy was more powerful than fairness, leading to a decision that most of us would see as immoral.”

You might argue that the moral knot here can be untangled by expanding one’s empathy to include all the children waiting in line. But this solution only returns us to the need for an application of rational equity: the tiebreaker between these children (or between the robot and Caleb) for whom we now feel maximal, equal empathy, is to objectively assess their medical needs. So why not just start with rationality and leave empathy out of it?

Ex Machina has been praised for raising complex questions about AI, consciousness, ethics, and humanity — but its subtle enquiries into the complications of empathy are, to my mind, the most interesting, for this reason: its nuanced portrayals of the manipulations of empathy wouldn’t work without our own empathy being manipulated in the process.

Imagine a pill that eradicates your empathy. You go to a cinema, swallow the pill, and spend the next two hours fully conscious of watching people pretend to be other people while reciting words someone else has told them to say. In fact, you aren’t really watching actors — you’re watching light shining on a screen, while sandwiched between strangers, waiting for the credits to roll so you can find a more productive way to spend your time. The cleaning products beneath the sink might be out of date, and you could hoover the lint out of the sock drawer.

A lack of empathy would diminish the pleasures of things like sport and sex, and it would all but destroy fiction. The tears that flow at the end of the movie and the laughter at a Wodehouse novel are fundamental to the experience of watching a film or reading a book. Exploiting empathy is how writers simultaneously entertain us with complex emotional experiences and challenge us with equally complex moral conundrums.

If part of you wasn’t cheering Walter White’s descent into drug lord violence, or smirking as the blood-soaked Carrie avenged herself against her bullies, that might be evidence of a lack of empathy on your part. And nuanced empathy leads to the simultaneous feeling of sorrow for the victims of Walter White and Carrie, creating the kind of moral dissonance that great fiction thrives on.

So, while we’d do well to eject empathy from moral reasoning, fiction would be obsolete without it — and we’d be impoverished for the absence of transformative fiction. Walt Whitman wrote in ‘Song of Myself’, “I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself become the wounded person.” Through fiction, we become the wounded person without the wound. We benefit from the experience without suffering the actual injury.

Ex Machina helps us see where empathy succeeds and where it fails. We find reasons to ignore it in questions of ethics, and why we can’t do without it in fiction, or in our lives more generally. Ex Machina reminds us that while empathy doesn’t tell us what we should do, it can tell us what we could do. Reason and logic will have to help us the rest of the way.

Some days I love Ex Machina, some days I despise it. I guess that’s why I respect it so much, it always tells me something different. I LOVE the book Against Empathy. I always recommend it (and I’m also using it for an essay on the dangers of fiction). Great use of it for this piece!!