On Collecting Books

On how we store books, the library as an anti-algorithm, and finding freedom in the finite.

My home library has always been carefully cultivated and clipped only under duress, but there was a time when it was culled from some fifteen hundred books to four. My wife and I were moving to Mexico, where storage would be an issue and we had to travel light, so the book-collecting of a decade came to an extended pause. We gave away so many books to our local bookshop that they finally told us they couldn’t take any more. We gave a huge chunk to our closest friends, also book collectors, and the rest went into a mere six boxes that we kept on the farm owned by my wife’s grandmother.

We set off for Mexico with only a rucksack full of clothes and a handful of reading material. For six months, I lived off of the four books I’d brought with me, as well as a small pool of circulating texts passed on to me by English-speaking travellers offloading novels to make space in their bags. The four books I’d chosen as my travel companions were Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace, Beware of Pity by Stefan Zweig, The Sea, the Sea by Iris Murdoch, and Ariel by Sylvia Plath.1

Each of those books is now inexorably entwined with a particular place. The thought of Foster Wallace’s endurance-test of a novel comes accompanied now by the feeling of my back on the bed, the only cool place to read when the sun became too much, and a respite for my weary body while my wearying brain struggled on. When I re-read The Sea, the Sea, I’m once again in a Mexican garden with an ocean of sky above and sun-bleached grass beneath my dry feet, floating in the scent of lime and basil and something familiar yet forever just beyond my ability to name it.

More than simply attaching a few books to a place, this exercise in literary asceticism functioned as other periods of fasting do — to remind me of what I value and why I value it. I decided to never again starve myself of reading, and that I would build my life around books. (Not incidentally, that time in Mexico was when Art of Conversation was born.) Once we returned to the damp climes of England, I set to work on building a lasting library.

Freedom in the Finite

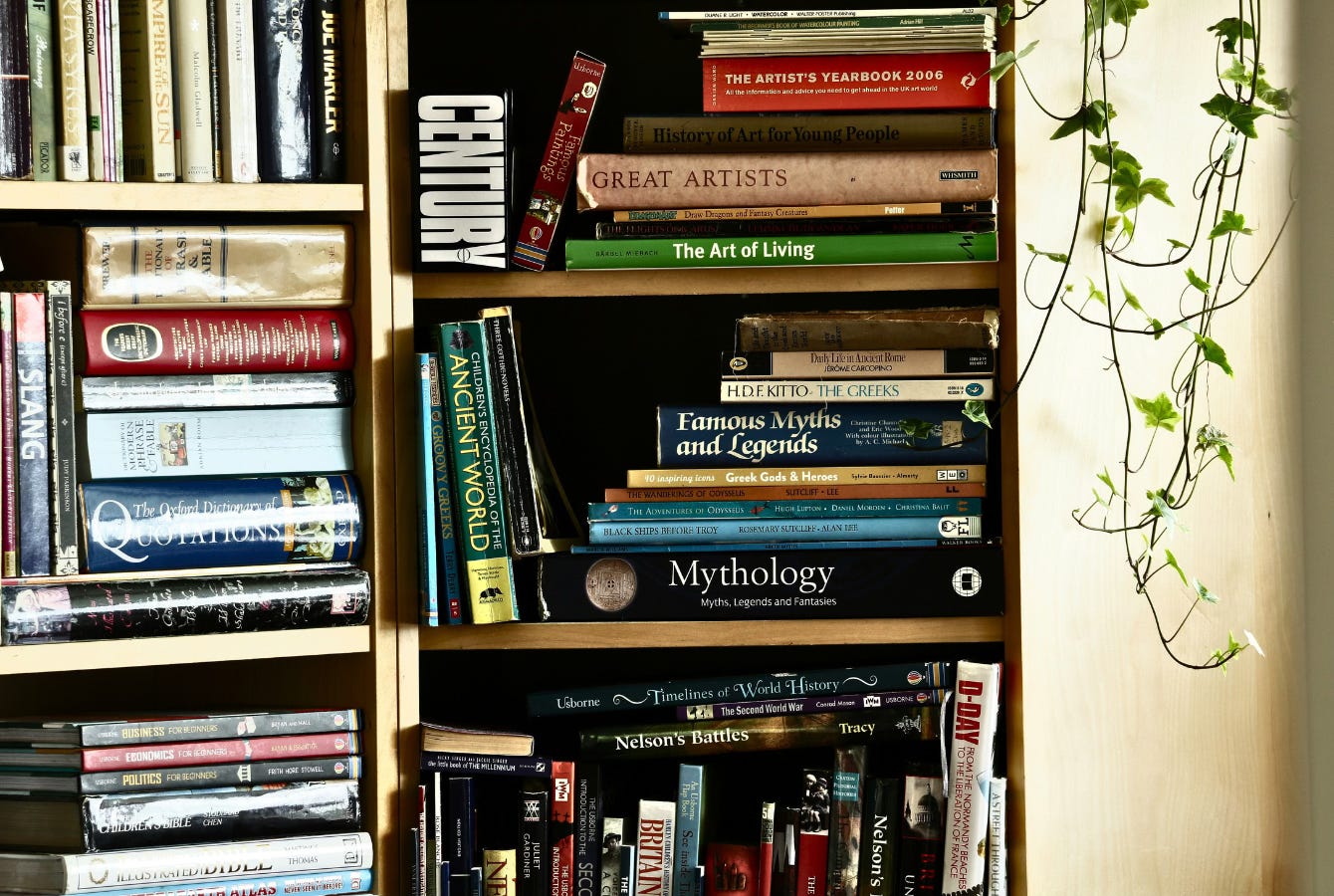

I began clearing space, building bookcases, and filling them with a growing collection of books both read and yet to be read. When you begin building a library of your own, you immediately collide with the limitations imposed by the physicality of books, as well as the shelves, bookcases, table tops, and miscellaneous surfaces required to store them. The more books, the more space you have to clear from your home and your life.

This is the most common reason given for turning to digital books, music, and movies. It’s here that the fracture line can be traced between consumers and collectors of a given medium. What divides them is whether they see the innate limitations of physical media as a negative or as part of the charm, perhaps even the whole point of it. The collector would say:

One of the things that makes analogue storage superior to digital infinity is that it imposes restrictions.

The most basic of these limitations is that we’re forced to consider carefully what we keep in our lives. Most of us don’t have a whole wing of a house in which our books can make a home, and many of us are lucky just to have a couple of bookcases. We have to make room for things, which means arranging them in an informal hierarchy of value. Do I want to have more books than trinkets in my home? Can I get rid of that old video game console and keep a few more hardbacks in its place? Do I really need that side-table, or can I rest my mug on a tall pile of coffee table books stacked next to the sofa?

The monetary cost is another limitation of physical books, and it engenders a deeper appreciation. Having spent money makes us pay closer attention to the book, because (whether we’re conscious of this or not) we hate the idea of wasting money. We want to justify the expenditure by making our reading last longer, or by looking more closely at what we’re reading. The sunk-cost fallacy (continuing with something you’d otherwise quit simply because you’ve paid money you won’t get back) works here as an advantage. It makes us stick with books for longer, increasing the odds of discovering that there are things to like in this book after all. Or we’re encouraged to take the time to work out why we don’t enjoy this book, which makes us better readers.

The consequences of corporeal existence — which in books is made up of wear and tear, stains, creased pages, and loosening glue in the spine — require us to give care and love to our library. There’s something wonderful about how books depend on us for our care. If not for my having rescued certain books from dusty shelves in dark bookshops, their spines would remain uncracked and their pages unturned, and they would have remained fallen out of memory. Like the proverbial tree falling in a forest, a book unread essentially doesn’t exist. When someone opens a novel, reads its pages, and imagines an existence for its characters and ideas, we bring that book to life.

This responsibility demanded of collectors is also a gift offered to them. It’s an incredible thing to take responsibility for something. As it takes, so it gives — it gives you meaning and purpose, which are so much more nourishing than a libertarian sense of freedom that lets you choose on whim and discard your choice just as readily. This is what I consider true freedom, or at least freedom worth wanting. It’s a freedom found in the finite, which liberates us from the endless and ultimately unsatisfying pursuit of more.

An Anti-Algorithm

In Packing My Library — which carries the subtitle An elegy and ten digressions — Alberto Manguel demonstrates a certain unease over his proclivity towards perambulating around a subject, exploring its many detours and byways, instead of driving straight at the heart of the matter. “I stop to admire a quotation or listen to an anecdote,” he writes. “I become distracted by questions that are alien to my purpose, and I’m carried away by a flow of associated ideas.”

The irony is that the roving curiosity he frets over is one of the greatest qualities of Manguel’s books. Reading him is like strolling with somebody who happens to be friends with everyone from Austen to Zola, whose mind is at home in both Athens and Jerusalem (while keeping a wary eye on Silicon Valley), and who is happily following the bumblebee flight of association through words and ideas.

This is also what a library provides: the serendipity of meandering aimlessly among your books, drifting from author to author, from one subject to another, from questions to answers that provoke more questions.

In a public library, a breakthrough discovery happens happily and haphazardly as the result of human error: a lazy browser picks up a book from one section and idly drops it off in another; you go searching for a manual on fly fishing and discover, improperly shelved, a book on taxidermy, and a new interest is born. Then there are all the books put in the correct place but that aren’t determined by your pre-existing tastes: you reach for a novel by your favourite author — let’s say Stefan Zweig — and are intrigued by the title of the neighbouring book, something called Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin. Perhaps a new favourite book, certainly one you’d have never sought out.

In our personal libraries, it’s not a case of discovering something entirely unknown to you — you did, after all, buy all of these books. But flaws in the analogue nature of the IRL search function (your eyes and attention) mean that chance and fate can step in. The books I keep piled on their side in the gap between floor and bottom of the bookcase are hardly glanced at compared to those at eye height. Others are shelved out of reach, and if I don’t have the energy to find a stool and climb up, I won’t be choosing those overhead books in this moment.

Just as mood can sway me to read one book or ignore another, I can be moved in mysterious ways by the various novelties of physical books. Their spines, lined up in rows and occasionally stacked on their sides, come in varying widths, colours, heights and depths on the shelf. Some have a matte texture my fingers enjoy lingering over; others have a sheen that suggests modernity, a book new enough that I might not have read it yet. The thickness of a novel might compel me towards it, if I have a week off and want to lose myself in a story of great scale. Then again, it might dissuade me if I’m pressed for time, or want something less demanding of my attention.

These are only a few of the incalculable conditions that can lead us to re-read a long-forgotten book; to finally pick up the novel we’d always intended to read, or that we’d promised a friend we’d get to; or to realise that the ideas in this non-fiction book by X casts a unique light on that novel by Y. Lacking the hypertext connectivity of a digital index or an online browser, we form our own shifting and efflorescent connections to and between books. This is part of the charm of physical libraries.

I think of this quality as an “anti-algorithm”. It’s a celebration of the randomness of life — which is, perhaps, ultimately knowable as some kind of quantum arithmetic, but which is, at the level of human experience, beautifully chaotic. We give our libraries structures and organisational devices, but as with all of our best laid plans, things can still go wonderfully awry. My mood interacts with my perception of a cover; the pressures of the clock restrict how many pages I’ll be able to read that morning; my wife has left off the shelf a copy of her favourite novel, which I still haven’t read but here it is, as if it’s waiting for me, so why not?

I could write a lot about the failures of algorithms (and others have already written much about their designed atrocities, such as pushing pro-anorexia videos to teen girls), but I’ll settle here for making a single point. The one thing that no algorithm has ever been able to do is recommend a book, or song, or film based on its own tastes. The most popular online algorithms show me only things that are like the things I already enjoy. But when a friend tells me about the deeply personal connection he has to the Robin Williams movie The Birdcage and how it relates to his father, I want to see that film because of what it means to someone I care about — even if it’s not the “sort of thing” I would have chosen for myself. A good recommendation can take you out of yourself and bond you with another person.

The fact is that digital libraries have yet to come close to matching the many variables of a physical library. Icons have to stand in for book covers, and these are poor simulacrums. Scrolling through a feed of thumbnails that are identically sized, shaped, and weighted (that is, they weigh nothing at all) is a soulless exercise. It lacks the essential features of moving physically through a room, pulling books off of shelves, touching their spines, moving your eyes not just up and down but across and diagonally. These online feeds are disenchanted libraries, ones and zeros on a screen we poke at. Useful, perhaps, but utterly without magic.

Someone once said that what you think about God is the most important thing about you. I don’t agree, but here’s a sweeping declaration of my own: the number and placement of books in your house says maybe not everything I need to know about a person, but it says a lot. There’s an episode of Friends where Joey meets a woman who doesn’t own a TV, and he asks, truly mystified, “What’s all your furniture pointed at?” When I walk into a home without books, I experience a similar sense of being lost, of having wandered from any familiar signposts. There are many of us for whom physical books do more than furnish a room — they furnish a life.

Further Reading:

• Packing My Library: An elegy and ten digressions, Alberto Manguel (2018)

Some readers will no doubt think that I should have invested in an e-reader. No.