"Asteroid City": A Road to Nowhere

On postmodernism as a cultural cul-de-sac, and whether Wes Anderson can find a way out of it.

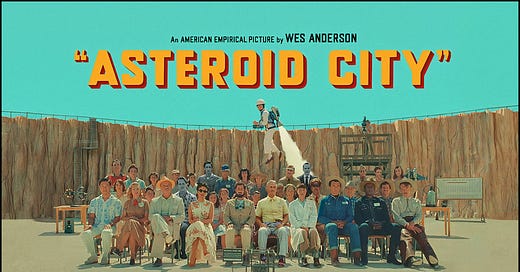

Asteroid City (2023)

Towards the beginning of Asteroid City, when we first arrive at the titular town, the camera pans and lingers in Wes Anderson fashion on key features, and we see something that explains the grand name of this tiny outpost: a half-finished bridge, complete on one side and suddenly, humorously, ending at its middle above the single road through town. A sign beside it says, “Ramp Closed Indefinitely”. This place is full of unmet aspiration and little else, a small town that once dreamt of being a big city. This image also serves as an apt metaphor for the film itself: incomplete, unfulfilled, promising something greater than it is.

We are brought into the town by way of a black-and-white introduction, which reveals that the film we’ve bought tickets to is not a film at all but a play whose production we are granted behind-the-scenes access to. So it was that first the lights fell in my cinema and then my spirits; few things are as certain to dampen my enthusiasm for a …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Volumes. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.