Hi everyone,

As September marks the dog days of Summer and life begins its slow fade into Autumn, this is always an apt time for reflecting on we’ve left behind. This year, we have the passing of Queen Elizabeth to reflect on, and with her the passing of everything her reign signified. We do still have something like a social fabric in our nation, though its threads have been remorselessly unpicked for the last half century, and part of ours has been made up for better or worse by the monarchy. With the thread of Queen Elizabeth II pulled from that fabric, many of us have taken the opportunity to take stock of what material remains.

For some, this has been a time of demonstrative mourning that often has the tenor of what is fashionably called "virtue signalling", although this has not been as melodramatic as the hair-rending and wailing that followed the death of Diana. For others, the queen's death is a chance to dust off long-held republican convictions and parade them as hot takes, and these often come off as the sneering, immature jokes and snide remarks that pass for commentary amongst the pubescent. Both of these extremes – the excessively, expressively grief-stricken and the horrendously crass – are manifestations of the unironic mind, which is forever thinking literally rather than laterally.

Such people fail to pass what F. Scott Fitzgerald described as "the test of a first-rate intelligence", which is holding two ideas in mind at the same time. As in: the monarchy is an institution we would do better without, and the queen was an individual, a person, whose death is the sad extinguishing of a human life. If nothing else, this at least is the lesson I am trying to take from the death of the queen. The queen is dead; long live the ironic mind!

Here’s to the passing of the old to make way for something new.

Matthew

Watching:

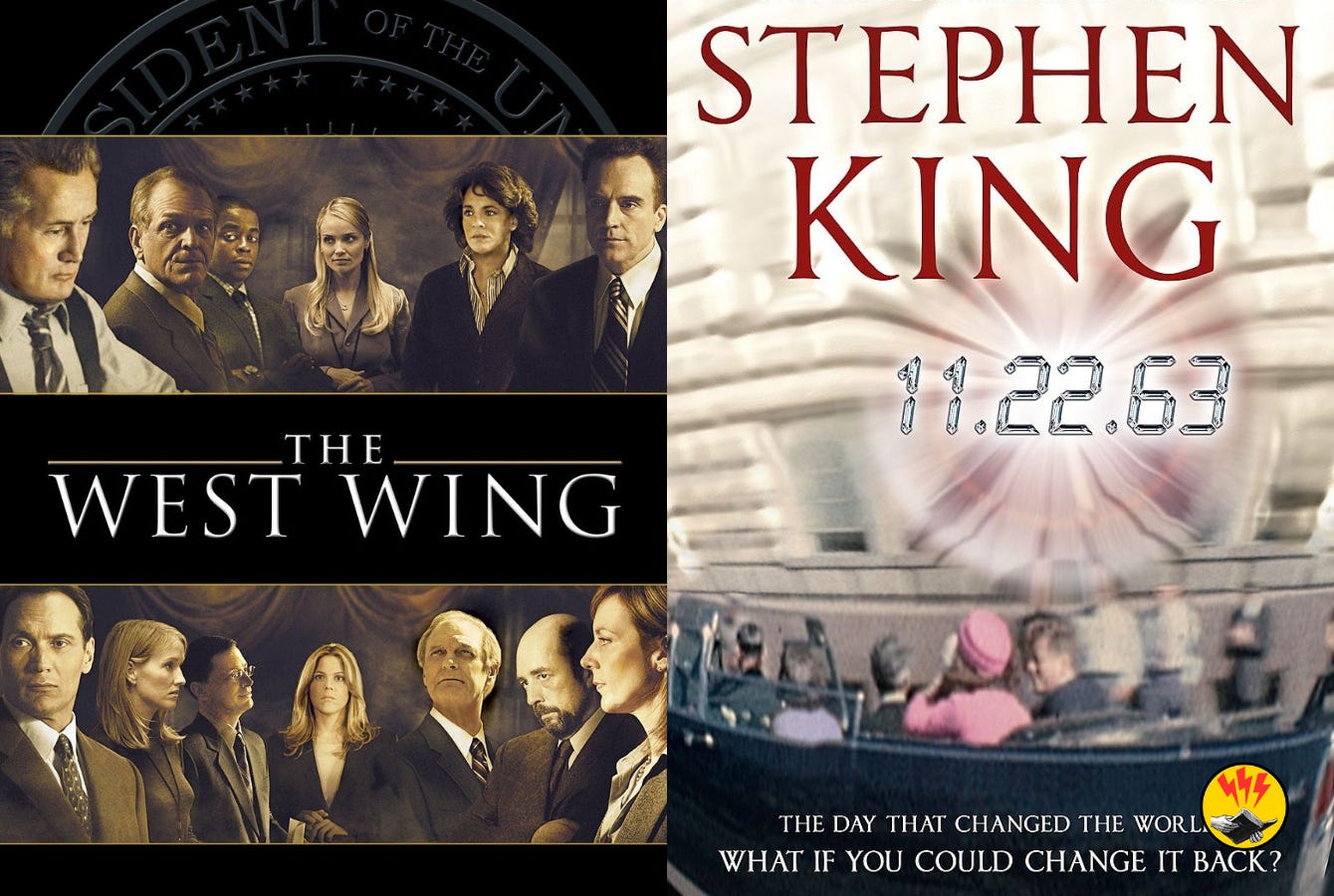

Kierkegaard once wrote that life must be lived forwards but can only be understood backwards. I was a teenager when my own forward trajectory took me through the years that The West Wing first aired. As a result, I had little interest in the show and its lightyear-a-minute dialogue, and I had even less ability to understand it had I tried. Now I find myself, crossing the halfway mark of my thirties, able to appreciate what I missed about the show back then. And I was missing out on a lot!

The series is pure liberal fantasy, of course: political disagreements between Republicans and Democrats are largely resolved by talking things out and by appealing to the decency of political opponents; every character has digested a thesaurus; the president has a seemingly photographic memory of every book he's ever read, which happens to be all of them. Although the world of the late nineties/early two-thousands provides wonderful escapism -- journalists make notes by hand and people consult books for information and no one checks their mobile phone every five minutes -- but the series isn't so much escapist as it is aspirational viewing. This is how we wish things could be: good people with sharp minds, big ideas, and witty banter setting the world to rights.

I can't help but watch this show with half my mind on the modern world, and comparisons between then and now are hard to ignore. One passing remark about the importance of the peaceful transition of power inevitably evoked the orange-faced spectre of 2020's president. But what I've really found interesting about this televised time capsule has been the reminder that time did not begin this second, and neither did the problems of global politics. It's refreshing to remember that just as the concerns of the pre-9/11 White House (fictional or real) can become entertainment decades later, many of our present anxieties will be ephemera that future generations might look back on with a wry smile. Or, true to Kierkegaard's dictum, might understand better than we can today.

Reading:

An update on a newsletter from a month or two back: I finished reading Purity by Jonathan Franzen and while he didn't quite stick the landing for me, which is to say that it didn't finish on a revelatory note that made me appreciate the novel any better than when I was in the middle of it, I did realise what my main problem with the book was. It was supposed to be funny. Not laugh out loud, Wodehouse at his best, comic writing, but it was a novel that wasn't meant to be taken entirely seriously. It's at least half my fault, because it took me longer than it should have to see Franzen wasn't quite hitting the realist notes of his other books, but even once I shifted gears in my reading to accommodate the borderline-absurdity of the plot and its characters, the novel still didn't land. I was reminded of Andy Miller's criticism of magical-realism, that it's neither realistic nor magical. Purity wasn't serious or funny. It seemed to be perpetually waiting for a punchline or a point.

On a more positive note, I've started reading the first Stephen King piece of fiction I've ever read. I have read his non-fiction, much of which is endearingly intimate and occasionally profound, but so far have not made it past the opening chapter of It and The Shining. So this month, I started reading 11.22.63 on the recommendation of a writer who said that this was his least "monster" oriented book, it's a love story, and it has the best ending to a novel he's ever written. I'm halfway through and I have to say I'm enjoying the hell out of it. I'm not crazy about the colloquial, chatting-with-a-mate style of narration he uses, and the prose doesn't exactly glow, and there's a certain dearth of anything like thematic or philosophical insight... but this is supposed to be a positive mention, so I'll admit that in spite of these failings, the man knows how to tell a story that grips you and won't let go. And that's not nothing.