On Gratitude: A virtuous cycle

On Douglas Murray's defence of gratitude, how being grateful resists the poison of resentment, and the reciprocal nature of appreciating the good in life.

In The Dark Labyrinth, Lawrence Durrell writes that the post-war world is on “a frantic hunt ... for the elementary feelings upon which any sense of community is founded”. This search for those fundamental values that might unite us and strengthen communities was provoked to urgency by their opposite – by the destructive tendency that had led the world into two wars, a tendency known to us as resentment.

In his 2022 book The War on the West, Douglas Murray takes a chapter to diagnose and properly define this sickness of the soul. Resentment is a destructive force that motivates individuals to deconstruct the presumed external source of one’s own inner agony. Or, as Murray describes it: “[Resentment is] blaming someone else for having something you believe you deserved more.”

Hitler played expertly on the national resentments of the German people, giving them a scapegoat onto which they could cast blame for all they’d suffered in the aftermath of the First World War. Lenin justified the communist regime in Russia, in part, by leveraging resentment from the proletariat against the bourgeoisie. In these ways and others, the poison of resentment had a vital role to play in the destruction across Europe in the twentieth century. And destruction, as Murray eloquently lays out, is always much easier than creation:

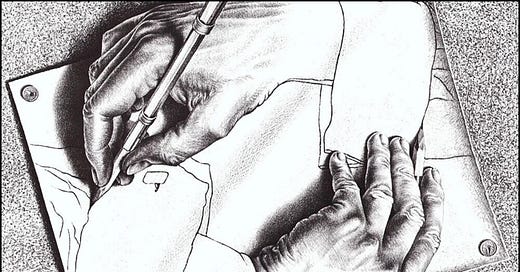

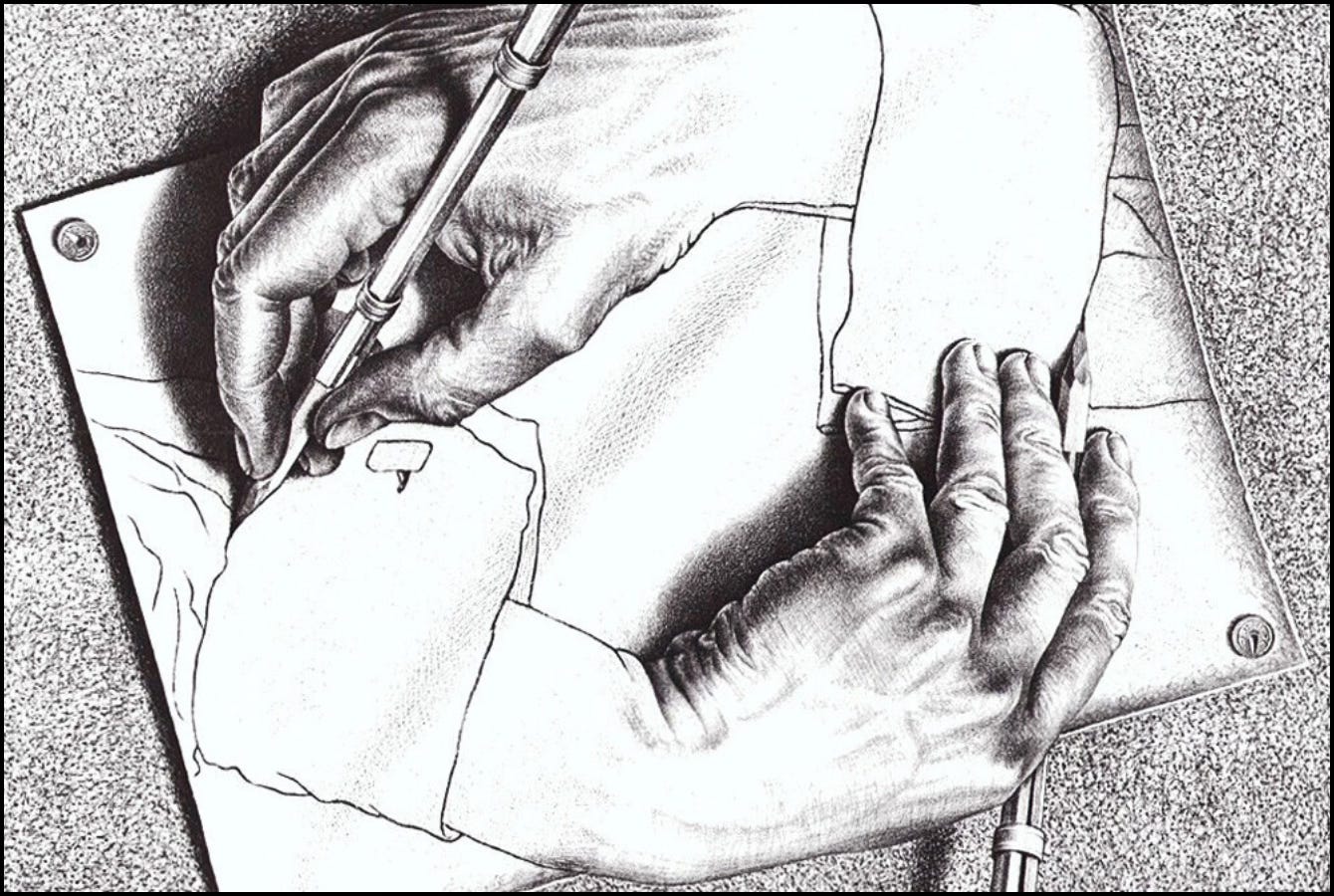

“A great building such as a church or cathedral can take decades – even centuries – to build. But it can be burned to the ground or otherwise brought down in an afternoon. Similarly, the most delicate canvas or work of art can be the product of years of craft and labor, and it can be destroyed in a moment.”

Murray adds that the same is true of the human body. In an account of the genocide in Rwanda, a gang of Hutus hacked with machetes at a Tutsi doctor and laughed at the sight of his brains spilling out on the roadside, mocking the fact that they’d belonged to a wise man. “All the years of education and learning,” Murray writes, “all the knowledge and experience in that head was destroyed in a moment by people who had achieved none of those things.”

Reading this, I was reminded of the Biblical story of Cain and Abel, brothers who bring offerings to God. Cain, a farmer, brings a generic gathering of fruits or vegetables; Abel, a shepherd, brings the best of his flock in the form of the firstborn sheep. This second offering is smiled upon by God, while the first is dismissed. Seeing how angry this makes Cain, God tells him that if he is hurt by this rejection, the blame lays with Cain alone; he need only do what is good and he will be accepted by the Lord.

But Cain is unable to do the emotional work of examining his own conscience and, in keeping with Murray’s definition of resentment as believing that someone else has unjustly received what you deserved, he turns on his brother. While out in the field, where no one can witness his crime, Cain murders Abel. Here – in wonderful microcosm of a kind that exemplifies the rich wisdom contained in even a few lines of an archetypal story – we see the weed that grows in the garden of every human heart.

We also see in this story the antithesis to resentment: gratitude. Abel does not give his offering to God out of a mere sense of duty or obligation, the kind that accounts for Cain’s lacklustre gift. Abel gives the best of what he has because he is inspired by gratitude to God for providing him with what he has in the first place. Gratitude invokes this desire to return some of the good that has been received, to bless the world just as you have been blessed.

Gratitude is a generative force, one that works against the urge to destroy. Grateful for the culture we inherit, we seek to preserve and contribute to it; grateful for the art, music, cinema, and literature others create, we want to respond to it and offer some of our own; grateful for the ability to thrive offered by our community, we wish to strengthen that community in turn. Gratitude, therefore, is one of the “elementary feelings” Lawrence Durrell wrote that the Western world was urgently seeking in order to rebuild in the wake of war.

Gratitude is also a choice, and it is harder to make than opting for resentment, because resentment lays the blame for one’s own shortcomings on external sources. The solution, resentment whispers in your ear, is in the hands of other people. You only need to point out how terrible they are, and it’s up to them to change. A reliable indicator of resentment is complaint without action. To choose gratitude, however, is not only to feel positively about the good that exists in your life, but to feel compelled to take personal action towards rectifying the problems that still exist in the world.

I grew up in conditions that could have made me resentful towards those who never veered as close to the poverty line as my family sometimes had. We always had a roof overhead, but threats of eviction were raised and sometimes the roof over our heads was not our own (the five of us lived for a while in the spare rooms above a church, and for a brief spell in a single room within the church itself). We always had money to live on each day, but it was rarely in any kind of surplus and it was attained through the incredibly hard work of my father who worked in factories, as a window cleaner, for the town council, as a handyman, and all the while as a homemaker for his four children. There is no monetary amount that can match the value of a dedicated parent.

I could feel aggrieved, if I chose, by the fact that I’d grown up without so much of what others around me had. There were times when I did feel resentful. This inevitably made me bitter towards those who came from money or whose parents had never divorced. Over time, I learned instead to value those things I did have, and that gratitude motivates me to raise others up rather than tear them down.

Sadly, many of those things we might otherwise feel gratitude for have been weaponised in recent years by reframing them as “privilege”. In an ordinary understanding of the word, privileges they certainly are, and that’s what makes them deserving of our gratitude. But the term has come to mean something we should feel guilty about and apologise for. Reframed in this negative light, imbalances in privileges are no longer to be addressed by widening the net of people able to enjoy them; instead, the solution is an attempt to bring down anyone benefiting from any privilege not equitably apportioned to all people. This is to cease to be grateful for what fortune we have and to engender resentment for all the luck we haven’t had.

To foster a sense of gratitude is not to deny the tragic nature of existence, nor is the bitterness of others reason to necessarily dismiss the things they blame for their ill-feeling. There is great evil in this world and countless problems to overcome, and occasionally deconstruction is needed in order to clear space for new constructions, to burn away the dead brush of bad ideas and failed institutions so that better ones might grow up in their place. What is called for is a sense of balance between gratitude for all that’s worthy of it and a recognition of the work still to be done. It is this balance that marks out our greatest artists, writers, and thinkers, who exhibit (in the words of Cyril Connolly) “a faith in human dignity, combined with a tragic apprehending of our mortal situation, and our nearness to the abyss”.

Caution at our nearness to the abyss, yes, but also gratitude that we have not fallen over it. We can see this full embrace of all that life offers, good and bad, in the last words written by the philosopher Roger Scruton before his death in 2020. Douglas Murray closes his chapter on gratitude with this reflection, and in a spirit of gratitude for the work of a man who I admired and yet frequently disagreed with, I will also leave the last words of my essay to Roger Scruton:

“During this year much was taken from me — my reputation, my standing as a public intellectual, my position in the Conservative movement, my peace of mind, my health. But much more was given back: by Douglas Murray’s generous defence, by the friends who rallied behind him, by the rheumatologist who saved my life and by the doctor to whose care I am now entrusted. [...] Coming close to death you begin to know what life means, and what it means is gratitude.”