Lazy and Stupid Stereotypes

On Michael Lewis, unsung heroes, and AI teachers.

“It may not be true that everyone in government who does anything especially useful starts out with a problem they want to solve, but it certainly helps.”

[Michael Lewis, ‘The Free-Living Bureaucrat’]

Not so long ago, I picked up a thin hardback in a bookshop because I wanted to know what its title meant: it was called The Fifth Risk. It was by Michael Lewis and it had something to do with why, actually, government bureaucracy is not only vital but incredibly interesting. I had my doubts, but I was in a mood to be persuaded. I took the book home, read it in two sittings, and learned a valuable lesson. If someone is offering to tell you why something you don’t find interesting or important is, in fact, terribly interesting and important, take them up on the offer. As a result, I’ve been giving away copies of the book to friends.

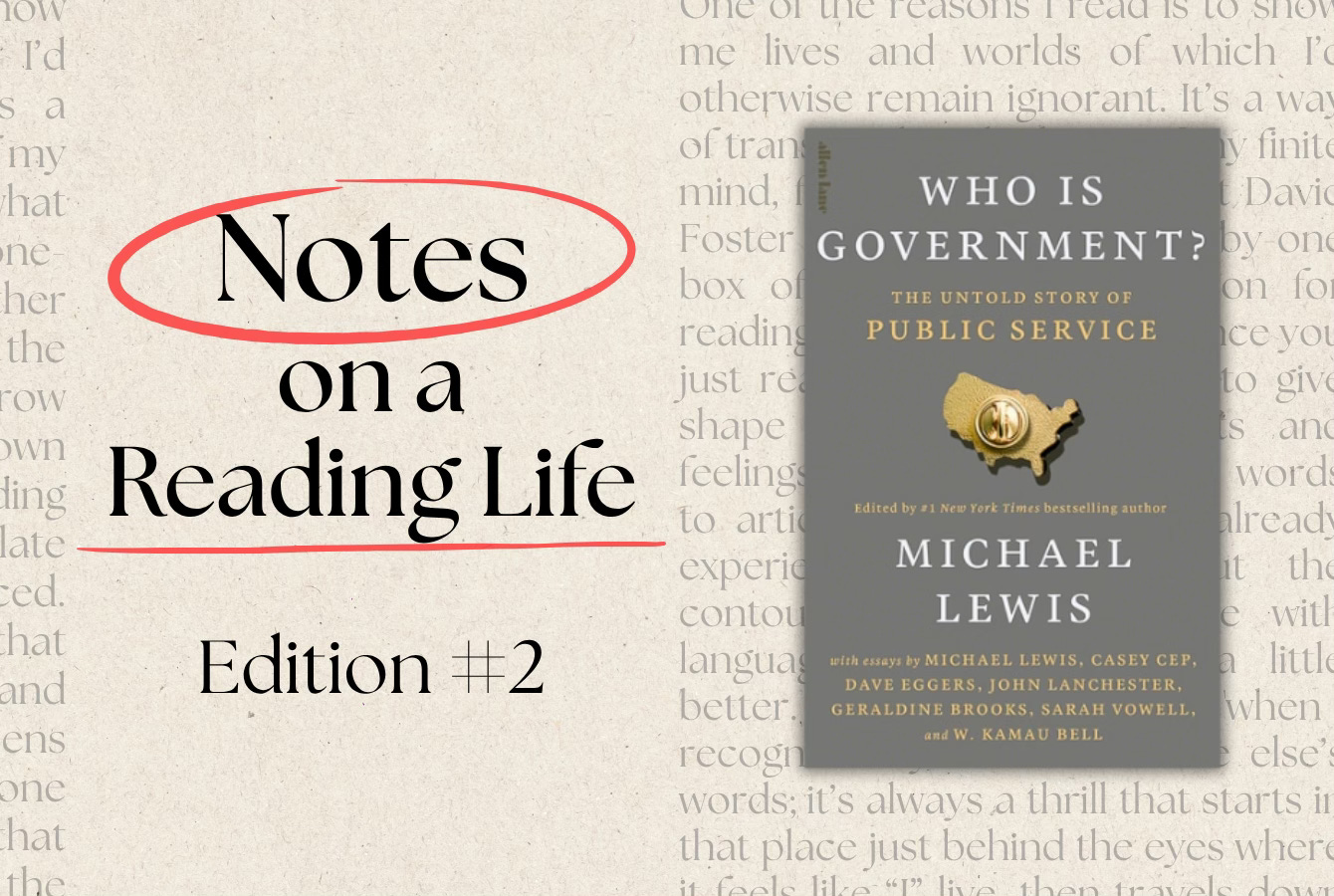

I’ve since read everything by Michael Lewis contained between hardback covers, and I was elated to discover that he’d just published a new one covering similar territory to that of The Fifth Risk. I had no concerns that this would be a re-tread rather than an exploration of new territories on the map of civil service, because the earlier book had shown that there’s no shortage of fascinating stories to be taken from the public sector. This was proven true when I read the new book.

Who is Government? is a collection of essays from various authors, and edited by Lewis, who contributes two essays. Lewis writes in his introduction about the stereotype of government workers as a “nine-to-fiver living off the taxpayer who adds no value and has no energy and still subverts the public will”. His ambition for the book was to “subvert the stereotype of the civil servant. The typecasting has always been lazy and stupid, but increasingly, it’s deadly”.

Each essay brings us the fascinating, inspiring, sometimes genuinely thrilling, story of an individual member of the US federal government. The aim of the book is to put names and faces to the indistinct mass we often picture when we think about the people who actually keep the country going. I was guilty of this before I read Lewis’ The Fifth Risk (which has the same goal as this book) — when I thought of government, I thought only of the blowhards and partisans on our TV screens. I didn’t think about people like Ronald E. Walters, who, in his role working for the National Cemetery Administration,

“has spent the past two decades obsessing over everything from the lifespan of a backhoe to how many days it takes to manufacture and engrave a headstone, working with scientists to determine what chemical best cleans marble, consulting with groundskeepers about the exact number of millimeters a grave settles every year, creating the 40 pages of standards and measures that regulate every national cemetery and then refining those standards annually to make sure that the agency is always improving the services it offers veterans at the time of burial and for all of eternity.”

If this seems tedious, you should also know that it’s what is required to maintain the incredibly high standard of the many veterans’ cemeteries around the US, and (if your into this kind of wonky stats game) to keep the National Cemetery Administration with a higher rating of Customer Satisfaction than any other organisation in the entire country. Not just the highest of all funeral homes, and not even the highest of federal organisations — higher than all organisations including Apple, McDonald’s, and any other public or private entity you can name.

Where this really matters, though, where the humanity beneath all the numbers is found, is in the work ethic encouraged by this attention to the smallest details. Walters, the hero of Casey Cep’s contribution to the book, shifts the praise (which turns out to be a common trait among these civil servants) to one of the many people working hard for his organisation, describing a technician at one of the cemeteries “who raced to the side of a woman during a bone-soaking rain”. He took off his boots and gave them to the woman so she could wade through the mud to find her grandfather’s grave. “He helped her find the grave, then stood in the mud in his socks while she visited”. Walters teared up telling the story, as did I on reading it.

I’m not a US citizen, but I am a citizen of the world and America is still (at the time of writing) the dominant global power. So what happens over there sometime matters over here. But more than that, the book is about how governments of liberal (at the time of writing) nations in the West function, or fail to function. There are, no doubt, unknown bureaucrats here in the UK doing just as vital — and thankless — work.

But there’s a second point I want to make about this big-hearted book: it need not convince you to adore the civil service to make it worth your time. Perhaps you’re an ardent fan of DOGE or of small government (cards on the table: I believe in the smallest government possible, which is not quite the same as the libertarian position, but that’s for another time). These human stories still reveal so much about what it means to be a person with a heart for service and responsibility, for “servant leadership”. There are myriad lessons about refusing to settle for “good enough”, achieving something worth striving for, and bringing the floor up for everyone around.

Not every essay in this collection lands (there’s a valiant effort to turn a number into a hero, but it failed, for me, to leap that tall building in its single bound), but the cover price is worth it for the last essay alone. It’s written by Lewis, and it’s the best kind of investigative journalism blended with riveting narrative non-fiction, weaving together three stories — any one of which on their own would have made for a compelling story — to say as much in 30 pages as other writers put in a whole book.

Also:

“Bill Gates: AI Will Replace Teachers”

An essay from , on the “horror disguised as progress” that is the replacement of human interactions with AI transactions.

Not only is this essay morally lucid and and intellectually clarifying, it’s written in prose that sparkles, full of sentences that distill whole arguments into debate-resolving finishers. As soon as I’d read it, I knew I’d be punctuating my future conversations about AI with, “Hold on, I have to read you this line from this essay...”

For some of my own thoughts on AI:

“What to do about the decline of the humanities.”

An essay from Henry Oliver on cultural cynicism.

Just as I was writing about Vivian Gornick and why her writing is wonderful and we should all read it, I read this essay over at

. In a nice moment of readerly serendipity, Oliver’s essay offered a concrete, real world manifestation of the principle Gornick writes about in her own essay. In short: take an active role in shaping the world you want, rather than reinforcing the world’s failures as they are.There seems to be an entire political philosophy that exists as a subset of “grievance politics”, which believes anger — on its own — is a form of political engagement. I keep meeting people who think of their outrage as something noble, as if mere anger does something out there in the world, and who look down on anyone less indignant as sheep following the apathetic herd. There also exists its cultural cousin, which looks on with disgust at cinematic remakes and the decline of a healthy, mainstream literary ecosystem and wishes — angrily — that things were better. And does nothing more than that.

The answer to this is both obvious (yet needs articulating, and needs it expressed as lucidly as Oliver does) and remarkably simple. The problems are complex and can seem overwhelming, but ultimately what we need to do in response is to pick one thing we can manage and just get on with it. Read a book if you wish people read more books. Champion that brilliant little indie film you think more people should see. Create a culture in your own life of valuing the arts and putting them at the centre of your social life, and see if that has an effect on the culture beyond yourself. Be an example of what works, not a perpetual critic of failure. As Oliver wonderfully puts it:

“If you think everyone is buying fool’s gold, then show them how brightly the real stuff can shine.”