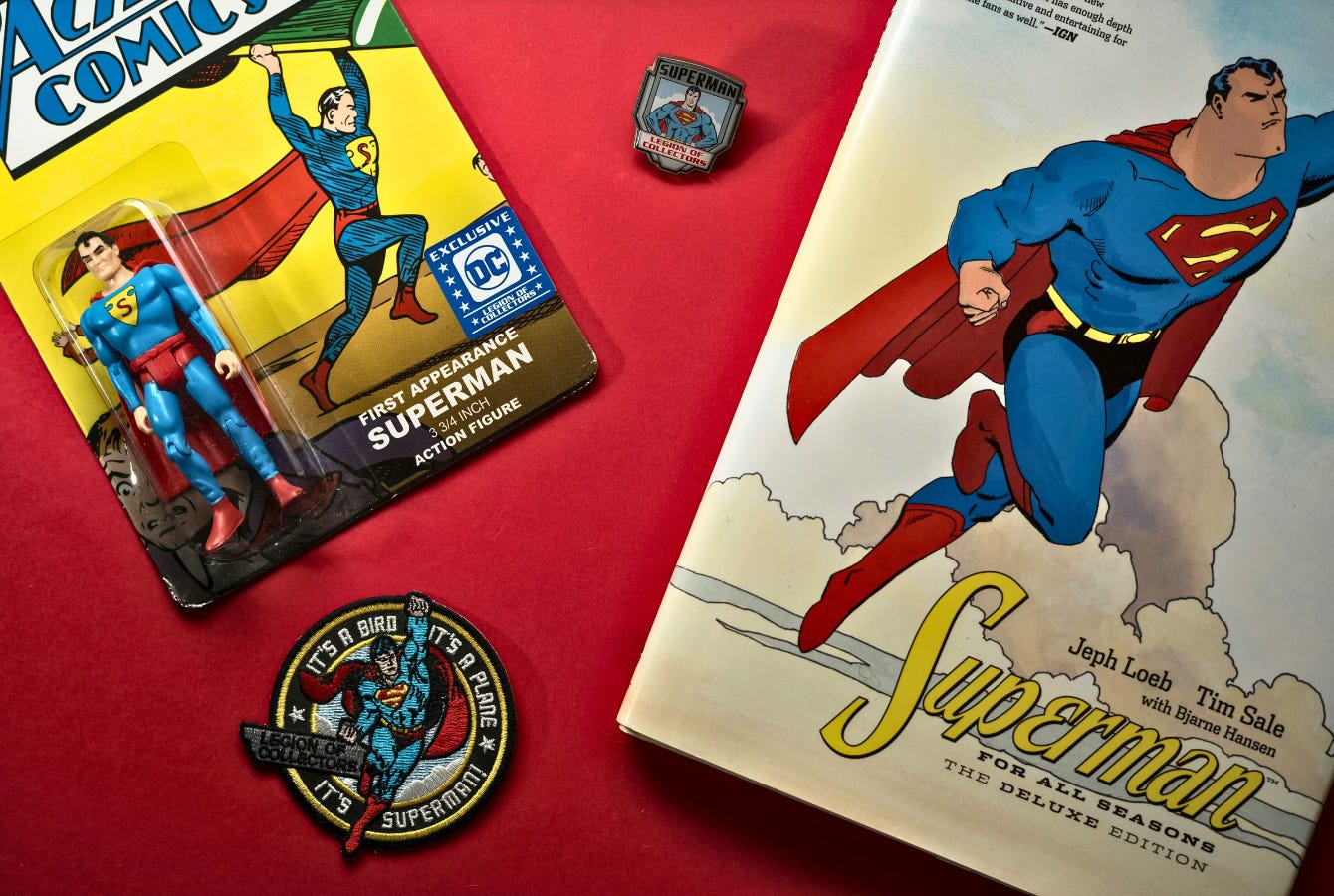

Asked, as a child, that age-old question If you were a superhero, which power would you want? I usually said I wanted to fly. Sometimes, I wanted Superman’s incredible strength. Occasionally, I wanted Batman’s gadgets, but that could instigate schoolyard holy wars between devotees of the various Marvel and DC gods about whether gadgets count as a superpower. Mostly, I daydreamed about leaping out of my classroom and into the sky.

When I watch a superhero movie today, I still thrill at seeing these semi-mythical figures perform fantastic physical feats. But that’s not what I find most impressive about superheroes now. I’ve put away childish thinking — if not childish movies — and I’m inspired by other virtues. Forget flying or x-ray vision; I want Superman’s selflessness, Captain America’s moral commitment, or Wonder Woman’s belief in the goodness of others. You can keep “faster than a speeding bullet”; I’ll take skinny Steve Rogers, facing a bully larger than himself, getting back up and insisting, “I can do this all day.”

This shift in my priorities isn’t so much a move from the grand to the prosaic, but coming to see the former in the latter. It’s a discovery of the sublime in the sublunary, an appreciation of the heroic in the ordinary. Sure, the moral questions these superheroes face are on a cosmic scale, their consequences reaching far beyond what anyone like you or me could ever hope to affect. But that’s what makes these figures mythological: they show us the ideal to reach for, always knowing we can never attain perfection, but striving for it as an act of hope, of faith. They show us how the world could be, to reveal how it should be.

Too often, however, the extravagance of the hypothetical — the fireworks and fistfights, the special effects and spandex — distracts us from seeing simple truth. There’s a story in the Bible about the prophet Elijah seeking a sign from God. A mighty wind came and shattered the rocks around him, “but the Lord was not in the wind”. Then an earthquake shook the mountain, “but the Lord was not in the earthquake”. After the earthquake came a fire, “but the Lord was not in the fire”. Then, after all of this, Elijah heard “a still small voice”. This was how God spoke to him. Sometimes, The Divine isn’t found in dramatic shows of great power but in the small, the quiet, the seemingly unexceptional.

Yehuda Amichai points to this in his poem “Tourists”, where he describes sitting with baskets of shopping under a Roman arch in Jerusalem. A tour guide says to his crowd, “You see that man with the baskets? Just right of his head there’s an arch from the Roman period. Just right of his head.” The poet believes that redemption will come if the guide would just tell them, “You see that arch from the Roman period? It’s not important: but next to it, left and down a bit, there sits a man who’s bought fruit and vegetables for his family.”

We often let grand narratives overshadow the wonder of the everyday, such as a man with no special powers or wealth working an honest job to bring food back to his loved ones, every single day. It’s easy for largeness and loudness to drown out the still small voice, the one that, in our best moments, shepherds the better angels of our nature. It’s worth remembering to turn our attention to the ordinary heroism and understated miracles of daily life.

In The Great Divorce, C. S. Lewis describes a heavenly parade in which spirits and musicians celebrate the procession of a great lady of “unbearable beauty”. The main character turns to his guide and asks, in trembling awe, “Is it? ... is it?” He presumes that she can only be the mother of Jesus herself. No, the guide says, this is Sarah Smith, who in life had been a suburban housewife. And what has she done to deserve such honour?

Through loving devotion, she was like a mother to every child she met; she inspired a kind of love in men that made them “not less true, but truer, to their own wives”; even animals were touched by her kindness. Her compassion was “like when you throw a stone into a pool, and the concentric waves spread out further and further”. She gave without holding back.

In Why Faith Matters, Rabbi

describes how his father, as a child, dealt with his own father’s death. The boy followed the Jewish custom of walking to synagogue every morning for prayers, a practice that lasts for a year after a parent has died. At the end of the first week, he left the house and bumped into the synagogue’s ritual director, Mr. Einstein, who said the boy’s house was on his way to synagogue. The man suggested they walk together, so neither had to be alone. Wolpe writes:“For a year my father and Mr. Einstein walked through the New England seasons, the humidity of summer and the snow of winter. They talked about life and loss and for a while my father was not so alone.”

The boy grew up, got married, and had his first child. He called Mr. Einstein to arrange a visit. Mr. Einstein, being much older now, asked if they could come to him. The family got in their car and made the journey, which was “long and complicated” — it turned out that the house Mr. Einstein had left each morning to meet with the boy was nowhere near the boy’s house. Wolpe’s father writes:

“I drove in tears as I realized what he had done. He had walked for an hour to my home so that I would not have to be alone each morning ... By the simplest of gestures, the act of caring, he took a frightened child and he led him with confidence and with faith back into life.”

I’ve been incredibly fortunate to have had many people in my own life demonstrate such selflessness and caring. I think of the music teacher at my school who opened the classroom on his lunchbreaks to teach me drums, lessons my family would have struggled to pay for privately. I think of the aunt who, though many time zones away on the other side of the world, was always available to take a phone call and guide me through my teenage crises. I think of my siblings, all of them raising their kids differently yet sharing one fundamental value: their children come first. In every choice, the wellbeing of their kids guides their purpose. I think of my own father, much like the man in Amichai’s poem, who worked hard in factories and for the local council so he could provide for his family every day. I never detected any resentment about the work, only love for the family he did it for.

Superman is fine for fiction. The real heroes are the ordinary people who show up to the task of living every day, who give without holding back, who love heroically — as though love were a superpower that might redeem the world. Their actions might seem small, but the hope they hold and inspire is epic.