"Petals for Armor": Why it hurts to grow

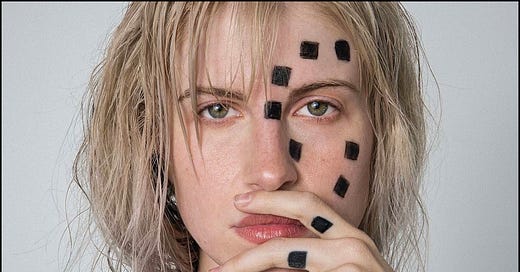

How Hayley Williams' intimate and personal music explores the pains and pleasures of growth.

1.

“I myself was a wilted woman,

Drowsy in a dark room.

Forgot my roots.

Now watch me bloom.”~ ‘Roses/Lotus/Violet/Iris’

Nothing in culture (from the expanding world of YouTube film criticism to the ever-diminishing book reviews) receives the same kind of interest as a debut work of genius, especially when its originating mind is so young that its wisdom seems like prescience. Not only does this author, artist, or musician know something important of what is to come, they seem also to be directing the path of the present into that exciting future. Aficionados are always eagerly waiting for artistic brilliance to burst out of virgin soil in shocking, landscape-changing full bloom.

I’m partial to unexpected genius from new artists too, but what really wakes me up is the complex, contradictory, mature yet still vivacious work of artists in that less-esteemed stage of life between young adulthood and life as a grown up. On the Road is an electric charge that got me going as a younger man, but K…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Volumes. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.