"Strange Heart Beating": By Any Other Name

On a debut novel that asks what our names and labels really tell us about people.

While we were living in Mexico, my partner attended a language school so that one of us could connect with the locals beyond the smallest of phrasebook small-talk. She began to notice the defiant and sometimes irritated way in which the Mexican teachers, hearing US students self-identify as “American”, would insist that they too were American. We wondered about this, because only a few months earlier, a man had won the US presidency in spite of (or because of) anti-Mexican rhetoric.

Perhaps this was an attempt to show that linguistic walls are as absurd as the actual wall Trump had proposed. Perhaps it was meant to reveal the inherent subjectivity in constructs such as American and Mexican, or us and them. Perhaps it was a rejection of the imperialistic way the US had commandeered the term “American” from people who’d occupied the continent long before the United States was born. Maybe it had something to do with how geography was taught in schools throughout Latin-America. Teachers described the Americas as just that – the Americas – without (as is the custom where I grew up) delineating between north and south.

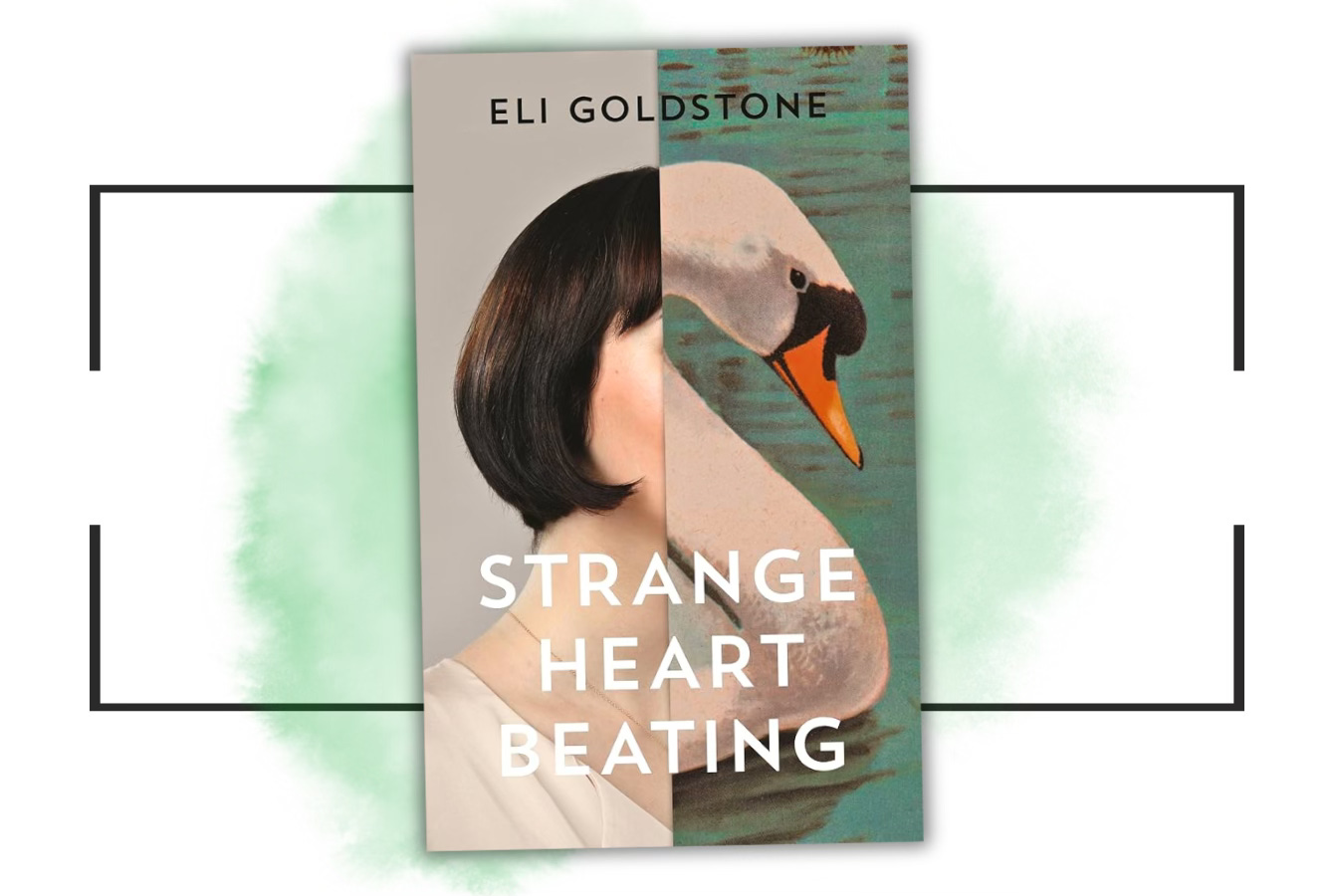

This question of why people choose to use one label over another returned to me as I read Eli Goldstone’s debut novel, Strange Heart Beating. In it, Seb’s wife has been killed while out boating by an angry swan, a farcical tragedy made more absurd by the fact that her name was Leda – as in she of Yeats’ poem ‘Leda and the Swan’. As he tries to make sense of this senseless loss, Seb obsesses over the esoteric details of their relationship, hoping to keep his wife alive by claiming ownership over her story.

This folly is undermined on every page by revelations showing that he knew only what mattered to him: that her name came from the story about Zeus and the swan, or the way she moved her hands while speaking of her childhood in Latvia. Excavating her past like the archaeologist of his wife’s life, Seb discovers her real name was Leila, and that he knows nothing of the past she spoke of while he fixated on the shape of her hands. The inspired idea Goldstone adds to her examination of the truism that other people are unknowable is the role that names and labels play in knowing (and failing to know) ourselves and others.

Leda’s names are central to Strange Heart Beating. Early in the book and early in her life, she writes in her diary that she’s begun addressing her mother by her first name. “Petra,” she says in a mature tone of voice, “hand me that glass please.” Young Leda is asserting pubescent autonomy by negating the familial link between herself and her mother. Her mother, with cutting and simple ingenuity, unstitches all this weaving of Leda’s character by responding, “Thirsty work, Daughter?” performing the same linguistic trick in reverse. Her intent is not to negate her daughter’s autonomy but cling to what connects them by language.

In The Good Soldier, Ford Maddox Ford defines love as the desire to identify with the object of that love. The lover, he writes, “desires to see with the same eyes, to touch with the same sense of touch, to hear with the same ears, to lose his identity, to be enveloped”. This is what Seb did when he first met Leda, cataloguing every detail of trivia connected to her in a way he’d “only ever experienced previously with academic subjects”. In the face of our limitations, we attempt to know and, at the same time, be known. We desire to mend the existential tear in the fabric of our existence – the divide between “me” and “you” – by projecting ourselves into and onto the minds of others.

This is what naming the world does: it describes the contents of reality in terms that convey our experience of those things. In most of our colloquial lives, we don’t attempt to communicate how something actually is, but how it is for me. We yearn for this because, as Ford writes, “we are all so afraid, we are all so alone, we all so need from the outside the assurance of our own worthiness to exist”. In these words, we glimpse the strange heart beating deep within religion, love, and art. Leda affirms this in the novel when she explains that the reason she writes her diary is “not that I want to keep secrets but that I want to be understood”.

However, it’s clear that Leda wants to be understood not as she actually is but as she desires to be. Changing her name from Leila to Leda not only assigns her the tabula rasa of a forged identity, it rids her of the moniker she hates, which she describes as a “jarring sound, spoken aloud”. This awful name is attached to awful memories: young Leila was abused by her psychopathic cousin, Olaf. After learning she hates her name, Olaf “pins [her] down and says ‘Leila, Leila, Leila’. It is worse than the other things that he does somehow”. And when Leila notices a classmate is missing a tooth, she wonders if “maybe something horrible happened to her, too”. So much is revealed in the simple adverb, “too”. The girl named Leila is the victim of unnamed traumas; the woman calling herself Leda is unmoored from her terrible past.

In one passage of the novel, Seb notes that “there’s no neutral vocabulary”, a claim that’s examined with deft and subtle sardonicism in the chilling light of changing social attitudes towards rape. Art historians have classically interpreted the event from which Yeats draws his poem as an act of passion rather than possession, rapture and not its etiological twin of rape. Look at the manner in which Goldstone delivers this dichotomy:

“We say that Zeus seduces Leda, we say he was her lover. To rape: to steal. From the Latin, raptus: seized, carried off by force.”

Goldstone places sensual phrases within an elegantly balanced sentence, which is then juxtaposed with the disjointed dictionary presentation of cold terminology. We disguise the ugly truth in the agreeable dress of poetic language, while a clear-eyed look at reality necessitates words that capture, rather than conceal, the strange heart beating below.

Seb turns the swan of the poem into the swan that killed his wife, imagining the act not as sexual but mortal. The phallic is “transformed into a sword and plunged by some force off-canvas into the body of my wife”. Leda’s death becomes a story; he even calls her life a “narrative” interrupted in medias res. Doesn’t this diminish her existence, by relegating the actual to the imaginary, by turning the rightful property of one (her life) into the appropriated possession of another (his story)? Perhaps. It’s a protective measure of distancing himself from the full weight of his loss. She’s a character killed by a malevolent deity, while he remains an atheist. Her death becomes a story that he can reject – denial by another name.

I wrote at the top of this review that Strange Heart Beating is about the labels we choose to give things, but it’s more than this – Goldstone is interested in how we attempt to know ourselves and others through the names we give them. It’s also a novel about how we present ourselves to the world, and how the names we give things change how we perceive them. It might just be that a rose by any other name would not smell as sweet.