"The Darjeeling Limited": In search of what's missing

On Wes Anderson's 2007 film, The Darjeeling Limited, and how absence is at the heart of its story – and often at the core of how we understand ourselves.

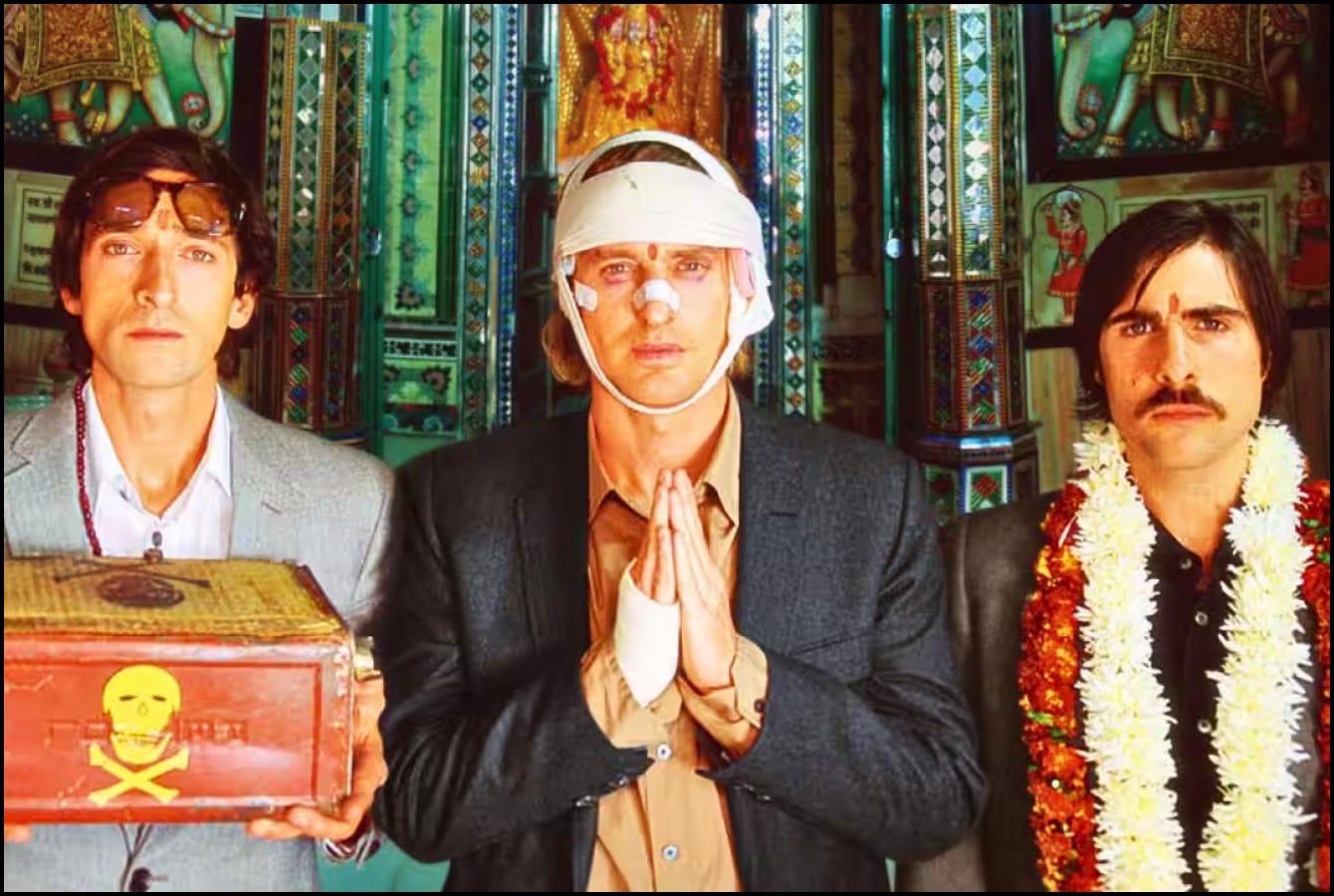

Nietzsche announced that God is dead; Freud told us that God is dad; in Wes Anderson’s The Darjeeling Limited, both are the case. Francis, Peter, and Jack Whitman have not spoken in the year since their father died. God is gone, and it is the task of the three brothers to fill the empty space this absence has left in their lives.

We meet Peter first, a man on the cusp of parenthood, racing an older man – standing in, perhaps,for an older version of Peter – to board a departing train, the Darjeeling Limited. Peter outruns the old man and, leaping on board, allows himself a self-satisfied smirk. By boarding the train and setting off across India with his brothers, Peter has avoided something he doesn’t want to look at. This is why he also doesn’t tell his brothers right away that his wife, back home, is weeks away from giving birth to his son.

What is it about fatherhood that scares him so much he goes halfway around the world to avoid thinking about it? We never find out directly, though there are plenty of valid guesses any viewer might take, and this lack of a script-supplied reason is one of the many absences that dominate thefilm. All we really know about Peter is that the death of his father defines who he is. His youngest brother’s first observation about Peter behind his back is that “he’s still in mourning”.

Jack, the youngest, is also mourning, though his is for the romantic relationship that recently ended. If Peter’s approach to grief is avoidance, Jacks’ can be said to be a sort of immersion therapy: While Peter is “trying not to get too caught up” in the fact that he will soon be a father, Jack immediately sets his focus on sleeping with the first train stewardess he sees. These two brothers are laden with loss, identified by it.

Francis, on the other hand, hides his loss with the cover of perpetual motion. He attempts to fill the emptiness with packed itineraries for their journey and their search for spiritual enlightenment. The contradictions this creates in his character are there to be read on his face, smiling winningly through bandages that wrap his fractured skull. This damage was wrought by a motorcycle accident in which he “skidded off the road, slammed into a ditch, and catapulted fifty feet through the air”.

It’s what comes after this accident that reveals what kind of absence is driving him: “The first thing I thought of,” he tells his brothers about waking in the hospital, “was I wish Peter and Jack were here.” This hits doubly hard if you happen to notice the line Francis drops into the middle ofhis account of the accident, when he casually notes, “I was going home. I live alone right now. Anyway,” and immediately moves past it.

The entirety of The Darjeeling Limited’s plot depends on the longing Francis feels to be united once more with his brothers. We learn late in the film that the last time these three men were together and bonded as a unit was on the day of their father’s funeral, a year earlier. They worked together, with none of the fighting and bickering that dominates their Indian journey, to get theirfather’s car out of a local garage, working together to push the vehicle onto the road.

But this scene also shows the cracks beginning to form: Jack implies that he may be leaving them soon, and Peter appears unhappy about this. The death of their father, then, is the fracture point in the relationship between these three brothers. A year later, on a train crossing a distant land, Francis hopes to mend the breaks and convince his brothers to fill the absence in his life that they left when they went their own ways.

There are many absences throughout The Darjeeling Limited, down to the details of the assistant who is supposed to never be seen, and who has alopecia with resulting baldness. Wes Anderson is a master of the particular, knowing the difference between a telling detail and clutter. His choices here all tell us something about the nature of absence. Like the hilariously absurd moment when Jack smashes a bottle of perfume from his ex, unleashing the stench of the perfume throughout their compartment, absence too permeates everything with itself.

As the film approaches its midpoint, the train itself reaches an apparent absurdity: It gets lost. “How can a train be lost?” says Jack, voicing the obvious. “It’s on rails.” As other men consult maps, the brothers wander the surrounding desert aimlessly, until Francis gets excited by the symbolism he hears in a phrase uttered about the train and its situation: “We haven’t located us yet.”

Francis is susceptible to seeing the profound in the mundane, clearly one of countless Westerners who believes he will find something enlightening in the exotic. But he has seen something at the heart of his own situation and that of his brothers – an absence of self, a loss of identity. As Anderson reveals in moments that gleefully mock the “spiritual quest” types who ditch jobs in marketing for yoga retreats in India, Francis hopes to “locate himself” through pseudo-spirituality, in various rituals he treats as if tossing a penny into a wishing well.

The brothers go into the desert and attempt a ritual involving a peacock’s feather, manic dancing, and seemingly improvised chants. Having claimed they’d read the instructions Francis gave them, Jack and Peter both make a mess of the ritual, leaving a dejected Francis feeling he has fallen right back to the emptiness where he began. “I did my best,” he sighs, “I don’t know what else to do.”

For all the humour and bathos of the scene, there is in Francis a genuine sadness that reveals how much he sincerely hoped to find something real. He reminds me briefly of R S Thomas, the Anglican priest who wrote so beautifully of the absence that defined his faith. In “The Empty Church”, we read of the search for God in liturgy and ritual that echoes the faintly ridiculous efforts of the three brothers in The Darjeeling Limited:

“They laid this stone trap for him, enticing him with candles, as though he would come like some huge moth out of the darkness to beat there.”

But these rituals, intended to bring to us the Divine, all fail. “He will not come,” the poet goes on,“to our lure.” Faced with this failure, the brothers resign themselves to the forlorn fact that absence will remain in their lives. “Let’s just find an airport and go our separate ways,” Peter says, after they’ve been kicked off the train and their efforts to achieve enlightenment have foundered. But this embrace of the absence is not the end of the poem, which goes on to ask:

“Why, then, do I kneel still striking my prayers on a stone heart?”

And this is not the end of the road for the brothers, either. The human spirit abhors the vacuum born of a loss of meaning, which it resists with the impulse to action and to belief – two components of the human experience that are more entwined than we might think.

Francis, Peter, and Jack trudge across the strange land they are strangers in, having abandoned their quest for unity and wholeness, when they notice three young boys attempting to cross a wildriver on a makeshift raft. A rope snaps, the raft capsizes, the boys are thrown into the air, and theyland in the violent waters. The three men immediately, instinctively, respond to a single cue: “Go!” Peter yells. They tear off and dive into the river, each of them struggling to pull a child to safety.

In spite of all their planning and itineraries, the brothers failed to make any kind of spiritual connection with themselves, let alone with each other; faced, however, with a real-world problem that requires immediate action, impulse alone is enough to make it happen. The best laid plans often go awry, but there is something beneath the planning, beneath our words and ideas and ceremonies and rites, something primal within us that knows enough to act without knowing all.

This is something like the faith R S Thomas held, which was the foundation of his stance in the world even when (as he writes in “The Absence”) “my equations fail as my words do”. All he ultimately has – just as all that any of us have in the face of meaninglessness – is “the emptiness without him of my whole being”. This is a negative with the weight of a positive. “It is this great absence that is like a presence,” Thomas writes, “that compels me to address it without hope of a reply.”

So which is it, given that I have advocated two approaches here: Do we reject the absence or embrace it?

To answer the question of whether to avoid or accept any given absence, we should turn to the one big absence in the lives of the brothers that we haven’t yet addressed – their mother. Neither parent was present a year ago on the day of their father’s funeral. Their father can be forgiven as it was, after all, his funeral; their mother, however, never gave a satisfactory reason for not showing up, and the brothers have not seen her since.

As the film goes on, it’s revealed to us – and to Peter and Jack – that Francis has located their mother in a convent in the foothills of the Himalayas. When this fact finally comes out, Peter asks,“How do you even know she wants to see us?” Francis replies, “She probably doesn’t. But maybe she does.” This possibility is enough for them to go on.

When eventually the brothers track her down, their first real conversation with their neglectful mother is full of absences. Peter tells her about the son he is about to have, and – possibly out of real concern for Peter’s wife, probably as a way of getting him to leave – she tells Peter he should be at home with his wife. Peter responds, “You should have been at Dad’s funeral.” One absence isjustified with another, or at least one is used as a riposte to the other. When their mother balks at this and says, “So you came here to make me feel guilty,” Francis says, “We came here because we miss you.”

Their mother’s excuse for why she wasn’t at their father’s funeral is self-centred: She didn’t attend“because I didn’t want to. He was dead.” The fact that he, her husband and their father, was not there was why she decided not to be there either. And while it is not explicitly laid out, we can piece together the timeline to see that she likely became a nun after – and possibly because of – her husband’s absence in this world.

Finally, Jack asks, “What about us?” To this, his mother turns, looks over her shoulder at the empty space behind her, and points at it. “You’re talking to her,” she says of a nobody standing in the vacancy behind her. What she means is that her sons are addressing somebody who does not exist, someone they are imagining to be real but who is, in fact, absent.

“I’m sorry we lost your father,” she eventually says, notably not an apology for her own behaviour.“Yes, the past happened. But it’s over, isn’t it?” To this, Francis replies, “Not for us.” The past – which is by definition an absence, standing in contrast to the potential of the future and the beingof the present – is a negative with a positive charge, an absence with the weight and presence of something very definitely here.

Their mother has two tactics left in her playbook with which to avoid the presence her sons want from her. First, she suggests they will be able to express themselves more fully if they don’t say anything at all. This results in an absurd, new-age circle of silence in which they attempt to communicate through the absence of words. Her second trick is a simple vanishing act: When thebrothers wake in the morning, she is gone. The other nuns can’t tell them where their mother is, only that “she goes away sometimes”. Absence is one of her defining features.

At the end of the film, Francis, Peter, and Jack must decide what to do with all the absences in their lives, and they appear to take two approaches simultaneously. As they run after their final train, trying to board while it moves off without them, they are weighed down by their bags, which once belonged to their father and now act as their luggage and a not-too-subtle visual metaphor. Francis calls out, “Dad’s bags aren’t going to make it!” All three of them toss their baggage aside, ditching it for the freedom of running unencumbered and leaping on-board.

As they take their seats, Francis hands back to Peter and Jack their passports. This has been a stress-point for their relationship throughout the film, as Francis has taken it on himself to arrange their whole journey, order food for them (which Peter testily tells him not to do), hold onto their passports “for safekeeping”, and even ask them at the start of their journey, “Did I raise us? Kind of?” Here, at the end, Peter and Jack both tell Francis to continue holding onto their passports, accepting the pseudo-parental role Francis takes in their lives.

The absence of their father and the absence of their mother are each an opportunity for growth. With their father, they come to understand that some absences must be accepted, even embraced, just as they did by freeing themselves of their father’s baggage. Other absences can be filled, taken as spaces in which to grow, as Francis takes up the role of caretaker abandoned by their mother.

In any case, the absence must not become the heart of a life, which is nihilism. The hope to hold onto is like the faith of R S Thomas, who in spite of the empty church still struck prayers on his “stone heart”, hoping one of them would ignite, and who was compelled to address the “absence that is like a presence” even “without hope of a reply”. It can also be much simpler than this, a single word. “We haven’t located us yet.” There is the hope, at the end, always remaining even in the face of absence: “yet.”

Bibliography:

• The Darjeeling Limited, dir. Wes Anderson; written by Wes Anderson, Roman Coppola, & Jason Schwartzman (2007)

• “The Empty Church” & “The Absence”, in R S Thomas, ed. Anthony Thwaite (1996)