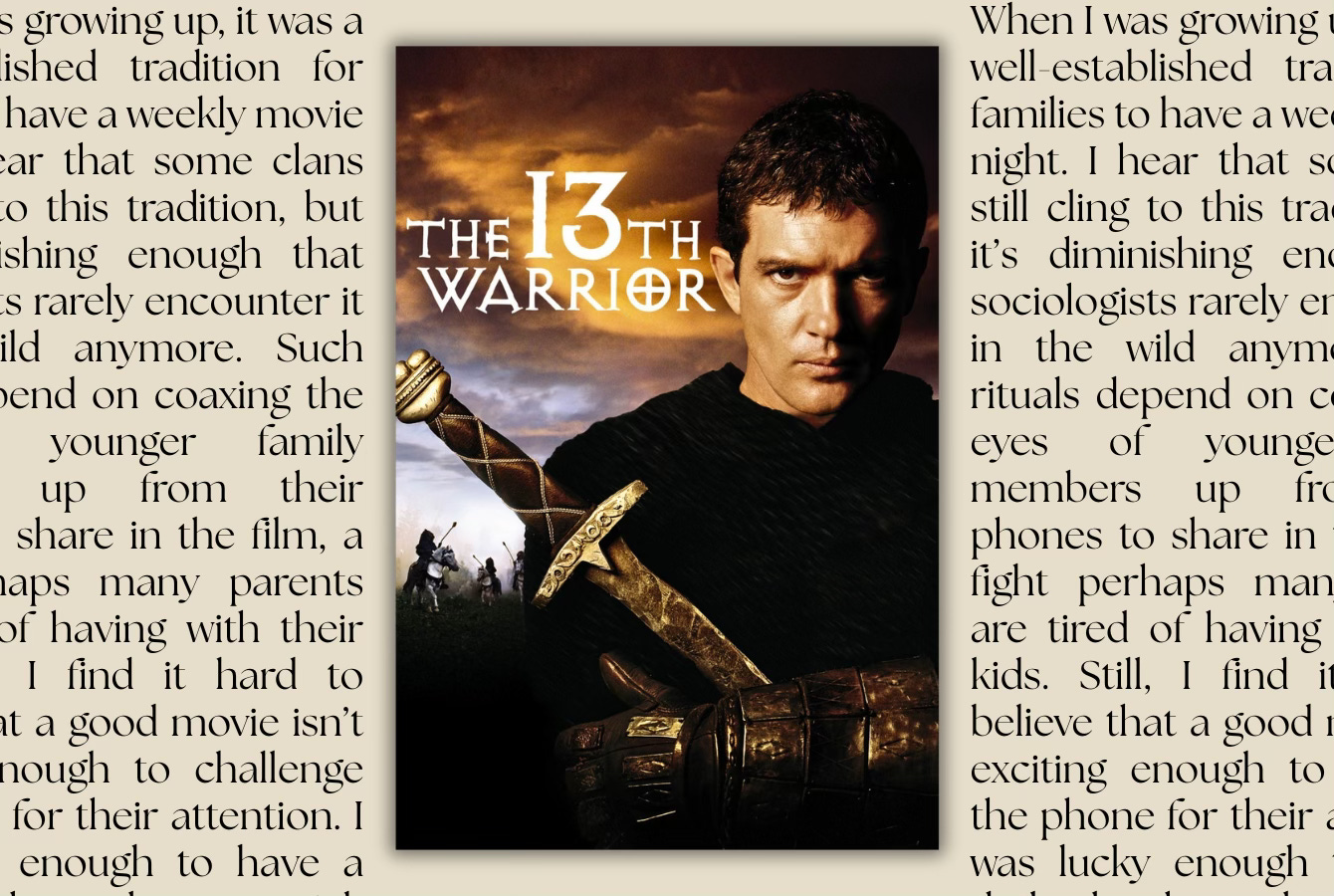

Re-watching "The 13th Warrior"

In the second edition of the series, I re-watch John McTiernan's 1999 movie, "The 13th Warrior", and wonder if it's time to put away childish things.

Welcome to the The Double Take, a semi-regular series in which I re-evaluate books and films that I first encountered long ago. Sometimes it will be something I loved and wonder whether it stands up today; sometimes it will be something I loathed and feel deserves a second chance. Today, a movie that’s “action-heavy and psychology-light”.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Volumes. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.