Re-watching "The Fountain"

In the latest edition of the series, I re-watch Darren Aronofsky's 2006 film, "The Fountain", and discover much more than a mere puzzle to be solved.

Welcome back to the The Double Take, a semi-regular series in which I re-evaluate books and films that I first encountered long ago.

Today, a film that’s gloriously singular, and unafraid of taking really, really big swings. Not all of its parts are perfect, but it adds up to something disarmingly sincere.

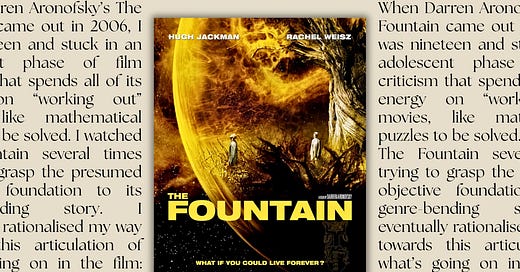

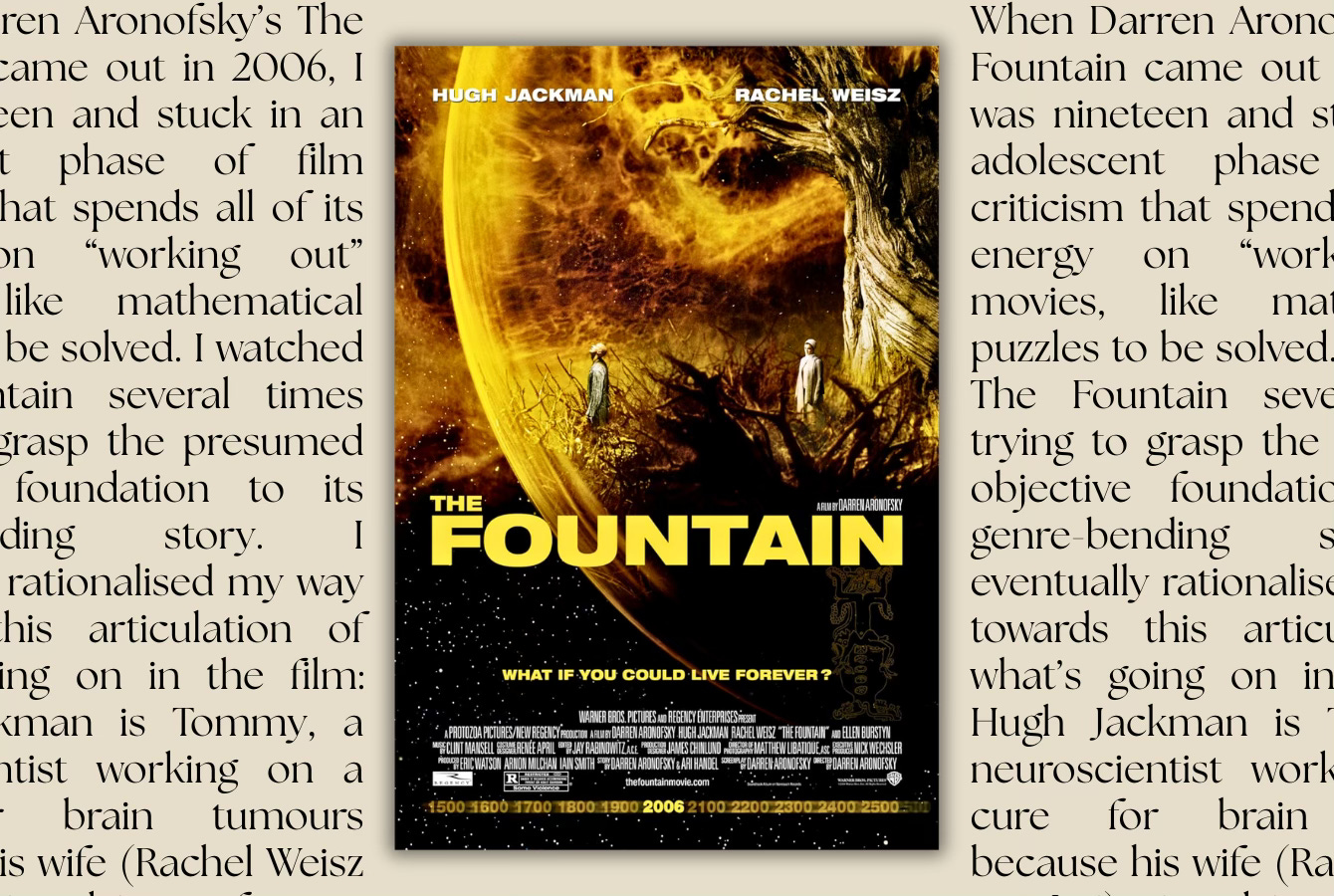

When Darren Aronofsky’s The Fountain came out in 2006, I was nineteen and stuck in an adolescent phase of film criticism that spends all of its energy on “working out” movies, as if they’re mathematical puzzles to be solved. I watched The Fountain several times trying to grasp the presumed objective foundation to its genre-bending story. I eventually rationalised my way towards this articulation of what’s going on in the film:

Hugh Jackman is Tommy, a neuroscientist working on a cure for brain tumours because his wife (Rachel Weisz as Izzi) is dying of one. Meanwhile, she’s writing a novel about a Spanish conquistador called Tomás (played by Jackman) searching for the Tree of Life so that he and Queen Isabella (played by Weisz) can live forever. Except this isn’t a fiction, because neuroscientist Tommy has a compound from a tree in Guatemala that might cure death. But Izzi dies, so once he has perfected and imbibed the cure, he ends up living through the death of humanity. Now, the last man alive, he drifts through space in a transparent bubble towards a dying star...

Because of the complex patterning of the narrative, it took me a while to knit this summary together, and while it made a certain kind of sense, it was fractured by inconsistencies. It also left me little to return to the film for — which is the key failure of this limited way of watching cinema. So I didn’t watch The Fountain again for more than a decade.

It wasn’t only that I felt I’d “worked out” the plot. I’d also moved away from the religious and spiritual stuff that The Fountain makes so central. At that point in my early twenties, I was suffused with the trendy cynicism of my generation, apparently (though not actually) disabused of my illusions about meaning, spirituality, and all the other kinds of fuzzy nonsense that The Fountain revels in. The path that had led me to that place of near-nihilism went back to my beginning.

When I was nine and my family moved across the world, we’d been told that God wanted us in England, and that all would be well because He had willed it. I grew up a little and learned something of family politics: it was no coincidence that “God” wanted us to emigrate to the country (and specific town) in which my mother’s relatives lived. I grew up some more and stopped believing in God. There was no meaning behind our move and its hardships after all, or there were only a few reasons and none of them good, which still felt like meaninglessness.

In my twenties, the uprooted sapling that I was began putting down new roots. I met the woman who eventually became my wife. Over the course of our relationship, I stopped viewing the series of events that was my life — leaving Canada, losing friends, the break-up of my family — as leading to meaninglessness; instead, they led to my meeting her. What had been a mess of confusion, pubescent hormones, and heartbreak was viewed now as fragments of the path towards the most meaningful relationship of my life. I knew we weren’t supposed to believe in meta-narratives anymore, yet I couldn’t help but see things that happened to me as chapters in the story of my life.

This narrative alchemy that turns the rough stone of events into the gold of life-stories is what Nietzsche argued made Greek tragedy an invaluable art-form. He claimed that spectators to staged tragedies looked into the abyss of meaningless existence and affirmed it, thereby affirming their own lives. It’s in reframing the tragic as an aesthetic performance that we can overcome its meaninglessness. Modernism and postmodernism have spent the last hundred years sacrificing artifice to “better” portray reality, and have ended up simply jettisoning art from its artwork. A slavish adherence to a bald kind of realism drains the mythic and metaphoric qualities from our stories, and metaphor is where meaning can be found.

Coming back to The Fountain in this later stage of life, I notice how all of these ideas about the transformative nature of art, and especially tragedy, are woven into the very fabric of the film. In the first draft of Izzi’s conquistador novel, her hero is killed by the guardian of the Tree of Life, who shoves a dagger into the coloniser’s gut. I’ve always taken this moment — cut off abruptly as it is — to be the point at which Izzi left off writing, having died before she could complete the manuscript. She’d spent her final days begging Tommy to “finish it”, assuring him, “You can. You will.”

Eventually, Tommy takes up the pen, and what he writes is his own epiphanic revelation: he doesn’t want to make the conquistador’s mistakes, which are Tommy’s own mistakes in different forms. Here is one of the incalculable miracles of tragedy that Nietzsche saw as indispensable to understanding life itself, which is that art makes participants of its viewers. Narrative demands that we interact emotionally and critically, rather than as passive observers. No lesson is so well learned as one that is experienced, lived.

In Tommy’s ending to the novel, the conquistador overcomes the guardian and approaches the Tree of Life with awe, before lunging at it with his dagger to greedily procure its life-giving ambrosia. As he gorges himself, he’s healed of old wounds and tastes a hint of the promised immortality. However, he falls to the ground in agony as flowers erupt out of him, feeding on his dying body to sustain their growth. Life necessitates death, this story reveals, and the closest we can come to immortality is in the life that follows our own lives, which depends on the efforts we make before we die.

The novel as finished by Tommy provides a lesson in negative; it’s the kind of story that shows us how not to live. In the end of the film, it’s this confrontation with the full truth of his condition — presented in the aesthetic spectacle of tragedy — that leads Tommy to finally embrace his mortality and see that there’s a certain wonder to the life cycle. “Death,” the film tells us, “is the road to awe.” And the truth is that, despite having seen this film a bunch of times before, and in spite of my prior cold rationality, The Fountain still made my lip tremble and caused a lump in the throat when Tommy finally accepts his end, having resisted human nature and its finitude for so long, and he does so with a smile on his face, even a laugh of relief, as he says, “I’m going to die.”

What The Fountain does so well can be understood in the dynamic between its two leads. We have Izzi and Tommy, the artist and the scientist. They represent what Nietzsche called the Dionysian and the Apollonian, and which I call Chaos and Order. The constant shifting of balance between these two opposing forces is seen throughout history and in each of our lives: we succumb to passions that rule us, or we close ourselves off to emotion; our freedom becomes a shapeless, meaningless hedonism, or our desire for control leads to the suppression of chaos under the despot’s boot. Nietzsche was convinced that great art is where Chaos achieves harmony with Order. It’s in literature, plays, music, operas, cinema, and all great works that these two forces interact productively to reveal what neither alone can show us.

In The Fountain, it’s only when the scientist takes up the role of artist, when the two poles become a unified whole, that meaning is finally found. In the film’s sci-fi sections, the film fully manifests that sense of meaning. Here, with Spaceman Tommy drifting alone through space, the sci-fi fantasy is transfigured into a kind of divine comedy: we see a man so obsessed with living forever that he ends up as the last man alive. He maintains his own existence by tearing apart the world around, feeding himself on pieces of a dying tree, until he’s finally able to accept death — and in that moment, he becomes whole. At a certain point, both extremes of the Dionysian and the Apollonian run out of road; escapism has limited potential, and (as we are discovering with increasing urgency) the pure reason of post-myth, anti-fantasy “realism” fails to speak of and speak to our deepest humanity.

Tommy the spaceman, the rationalist-in-extremis, floats through meaningless space in a self-constructed bubble. Tomás the conquistador rampages across the word in thrall to primal emotion, destroying all in his way and consumed by the cause. Tommy’s ultimate enlightenment comes as audience to a grand narrative, a work of literature (which is presented to us as a piece of cinema). He makes sense of his situation — as we make sense of the movie’s themes — by having it dramatised for him. The story makes sense of what had previously been meaningless.

I only came to read all of this out of The Fountain because I finally stopped puzzling over the objective existence of the spaceman and the explorer, realising that it doesn’t matter if the three Tommy characters are literally reincarnations of one person or actually one man who never died. I gave up on wondering what the “facts” of the story really are. What really matters is its meaning.

Further reading:

• The Fountain, dir. Darren Aronofsky (2006)

• The Birth of Tragedy, Friedrich Nietzsche (1872)