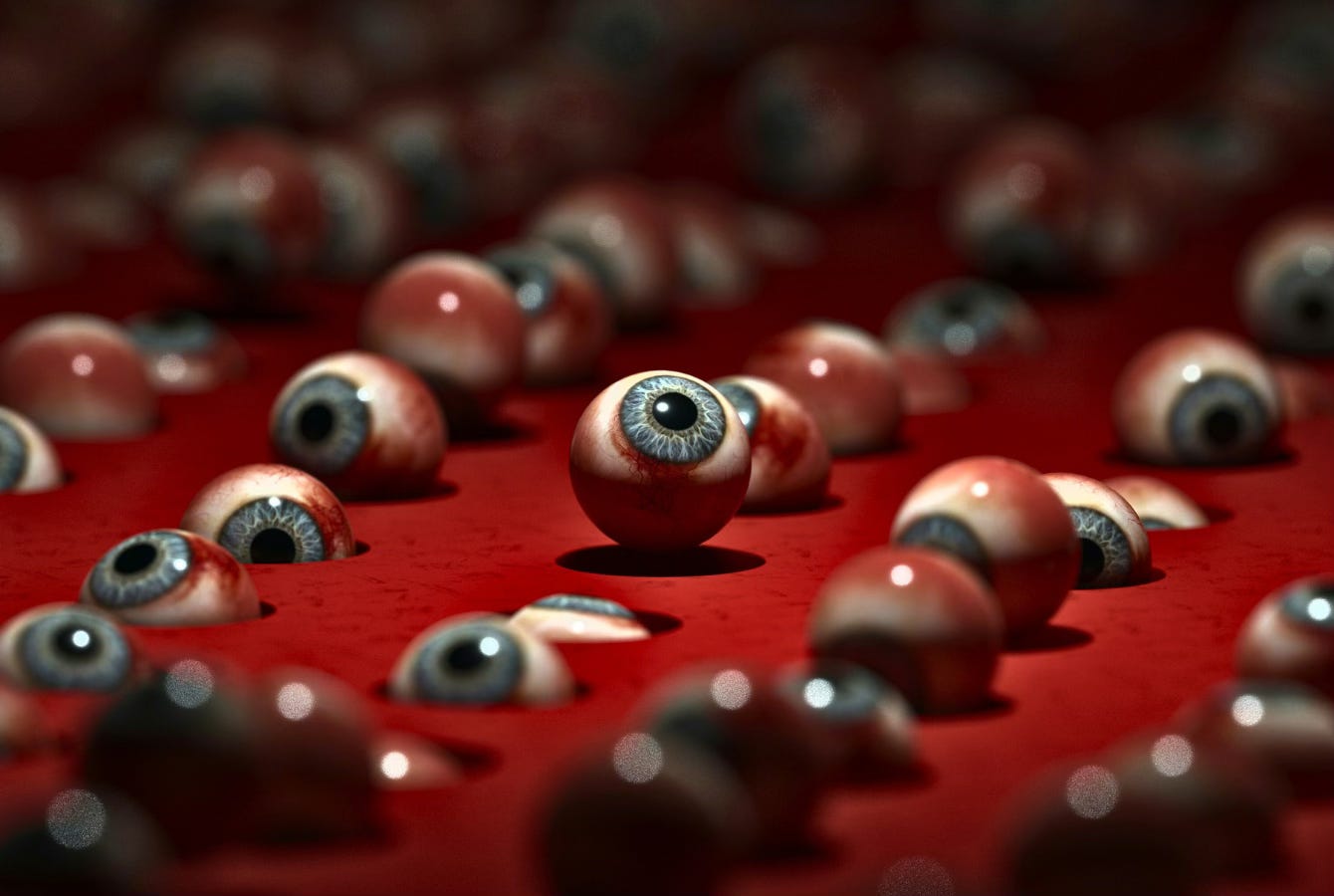

Who's Watching Who in "The Virgin Suicides"?

Let's talk about the most challenging — to some the most troubling — aspect of Jeffrey Eugenides' "The Virgin Suicides".

Earlier this year, a friend of mine read Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides and criticised it for perpetuating the male gaze. I returned to the novel somewhat sceptical of her claim but taking it seriously. While there are various ideas about what precisely constitutes the so-called “male gaze” and which works of art deal in it, I’ve always understood it to be essentially:

“The depiction of women in the arts as objects, often sexual, that serve the pleasure of a heterosexual male viewer.”

This is the understanding I brought to my latest reading of The Virgin Suicides, suspecting as I made my approach that one of my favourite novels was guilty of peddling this sexist paradigm. I remembered clearly the objectification of the Lisbon girls, who exist not as people but as objects relative to the subjectivity of the neighbourhood boys. I realised there’s an unhealthy romanticising of the girls’ pubescent ambience, recalling how the boys can’t stop reaching out for the sis…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Volumes. to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.