In a sharply observed essay called “Dumb and Dumber”, published in the late nineties, Bill Bryson wrote about a mode of “dumbing down” that has only increased in the intervening twenty-five years:

“A few months ago a columnist in the Boston Globe wrote a piece about unwittingly ridiculous advertisements and announcements – things like a notice in an optometrist’s shop saying ‘Eyes Examined While You Wait’ – then carefully explained what was wrong with each one. (‘Of course, it would be difficult to have your eyes examined without being there.’) It was excruciating, but hardly unusual.”

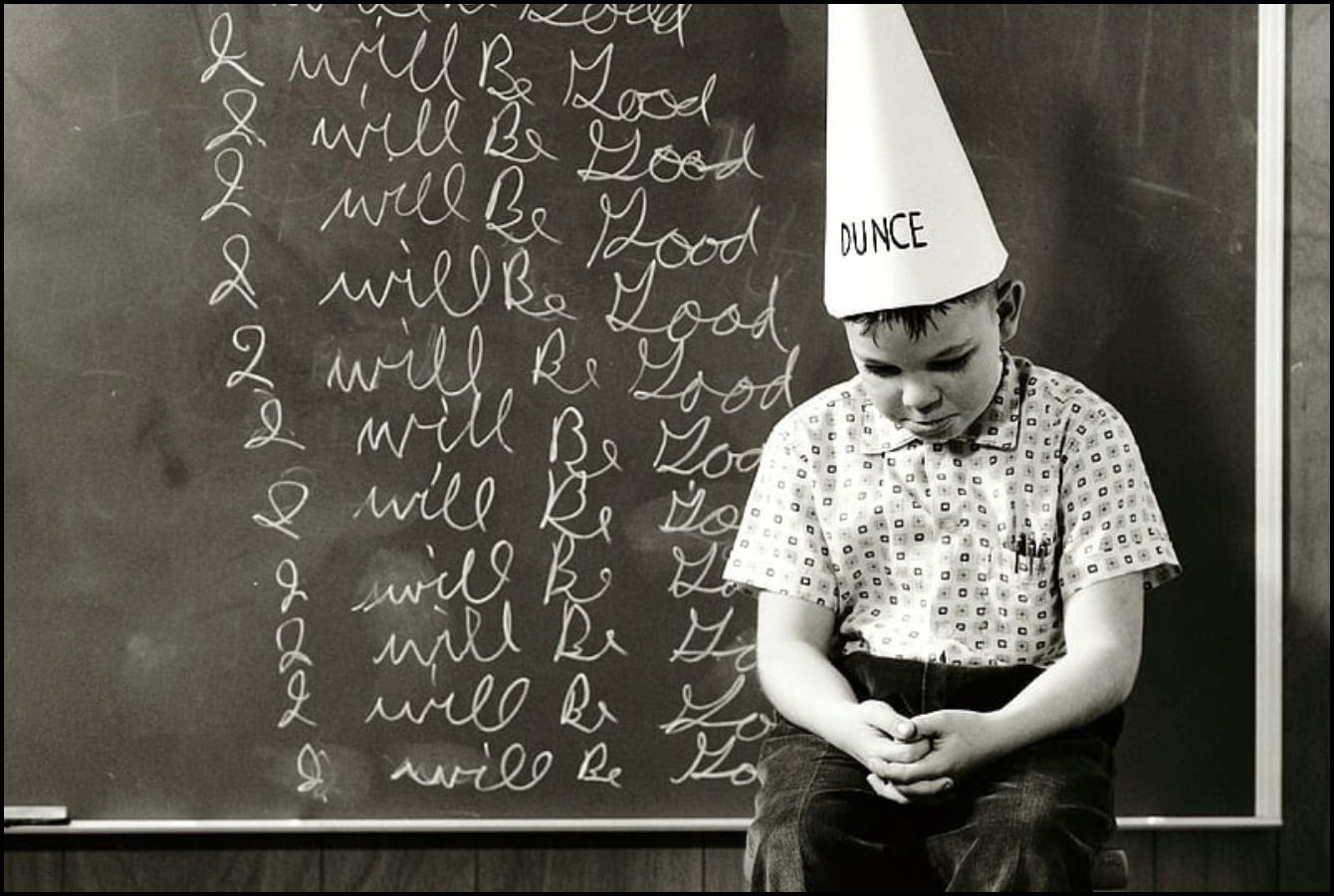

This article is part of a long-established phenomenon of society pointing out to us the mind-numbingly obvious. Bryson points out in his essay the myriad ways in which society in the nineties was already well along its seemingly-terminal decline into baseline stupidity. He notes how so much of the culture is geared towards preventing people from having to think for themselves. When a meteorologist on the Weather Channel informs the viewer that there are 12 inches of snow outside and brightly adds, “That’s about a foot,” Bryson wincingly thinks, “No, actually that is a foot, you poor sad imbecile.”

Bryson describes these prophylactics against independent thought as “crutches”, explaining that “the idea is to spare the audience having to think. At all. Ever.” Once you’ve had this pointed out to you, if you hadn’t already noticed it for yourself, it becomes impossible not to find these crutches all over the place. In a podcast I listened to recently, a guest littered her contributions with intellectual crutches, saying things like, “Bill Clinton – who’s a democrat – once said...” and, “George W Bush’s presidency was dominated by several large-scale events, like 9/11 and the Iraq War.” She was clearly well-intentioned, and no one could say that the substance of her work was superficial, but she kept explaining the basics as if concerned her audience would fail to understand otherwise.

Perhaps, however, this podcast wasn’t trying to let the listeners off the hook for thinking for themselves. Maybe it was simply reflecting the fact that many in their key-demographic would have forgotten certain facts from their cultural memory, many of them having been children or not yet born during the Clinton-Bush era. This societal amnesia is a topic that could have whole books devoted to it, but Alberto Manguel succinctly describes the historical context leading to our present moment in an essay titled “St Augustine’s Computer”:

“[For] the Greeks, who ... regarded the written word merely as a mnemonic aid, the book was an adjunct to civilized life, never its core; for this reason, the material representation of Greek civilization was in space, in the stones of their cities. For the Hebrews, however, whose daily transactions were oral and whose literature was entrusted largely to memory, the book – the Bible, the revealed word of God – became the core of its civilization ...”

We see Classical Greece building its culture around the mind; then Judaeo-Christian culture centring a particular set of texts; then the printing revolution expanding the cultural centre to include more books and more knowledge. With the internet, there are few restrictions on storage, on memory, on the capability to search for information, leading to a more frivolous view of what we now call “content”. That which we once wouldn’t have bothered to scribble as a note constitutes most of what we now tweet to the whole world. If the Ancient Greeks represent an age of deep thought, and the era of books represents one of disseminating thought, it’s hard not to view the internet age as one of triviality and amnesia.

The ease of access provided by the internet has led to what I call the Calculator Effect. Many of us who don’t “do” numbers and for whom mathematics is an unintelligible language have reassured ourselves that “we don’t need to know maths if we have a calculator”. Likewise, recent generations seem convinced that history is a thing we simply summon up with a Google search, so there’s no need to remember all those dates, names, and facts. Relieved of the need to carry in our head knowledge of a wide-range of subjects or a long view of history, we are less and less able to connect dots and see patterns, and we become more and more a culture obsessed with the present moment, the Era of Now.

All of which made it fascinating to read Bryson observing, in the nineties, the ways that pop-culture (and increasingly the general culture) relieved us of the need to think. We might wonder how that paved the way for the amnesia of today, ignorance begetting forgetfulness. Two further questions naturally arise from Bryson’s article. First, why is society doing our thinking for us? Second, why are we okay with this?

As I don’t wish to contribute to the culture of preventing one’s audience from having to think, I won’t supply my own answers here. I’ll just leave you with the questions.

References:

• “Dumb and Dumber” in Notes From A Big Country, Bill Bryson (1998)

• “St Augustine’s Computer” in Into the Looking Glass Wood, Alberto Manguel (1998)