A Day in Reading

On why we read, where we read, and how reading can change throughout the day.

SUNRISE

Today, I wake with the sunrise. Its light tells the resurfacing mind that it must return from the peace of sleep to the brilliant pace of day. Lawrence Durrell paints a sunrise on the waking page of Bitter Lemons (1957), one that looks “as if some great master, stricken by dementia, had burst his whole colour-box against the sky to deafen the inner eye of the world”. At first, I resist the sunrise and tell myself that I will determine what time I’ll roll from deep slumber to caffeinated consciousness. Then the alarm clock begins screaming like a drill sergeant.

For Nabokov, in King, Queen, Knave (1968), the clock actually breathes life into the world. His book opens with a “huge black clock hand ... on the point of making its once-a-minute gesture; that resilient jolt will set a whole world in motion”. As the dial turns to the number that signifies — arbitrarily and yet meaningfully — the start of another day, “iron pillars will start walking past ... the platform will begin to move past ... a luggage handcart will glide by, its wheels motionless”. It’s as if the timepiece watches from its static position while the world, on the clock’s instruction, comes to life and moves on.

My morning here is fictitious in its particulars, but it’s existed many times in its generalities. As I wake into myself, thoughts of the world and of the day ahead swirl through my mind as I silently watch. Some days, the play unfolding in my head tempts me from bed quickly, eager to start doing what I’ve planned; other days, the performance is grim, a re-enactment of previous grey days full of cold chores.

Happily, our day today, the one created for this essay, is a day full of books. This is one of those days that reminds me of being ten years old and waking miserably for school, before remembering, an ecstatic second later, that it’s the summer holiday. This is a morning born with a sense of freshness and possibility, like an empty canvas waiting for whatever I bring to it. In Max Porter’s Lanny (2019), this spirit of potentiality makes a painter exclaim:

“Ah, Lanny, my friend, look at these blank pages.

Don’t you feel like God at the start of the ages?”

God at the start of the ages, in my grander moments; a writer meeting with blank pages, more commonly; a person starting a new day, today.

MORNING

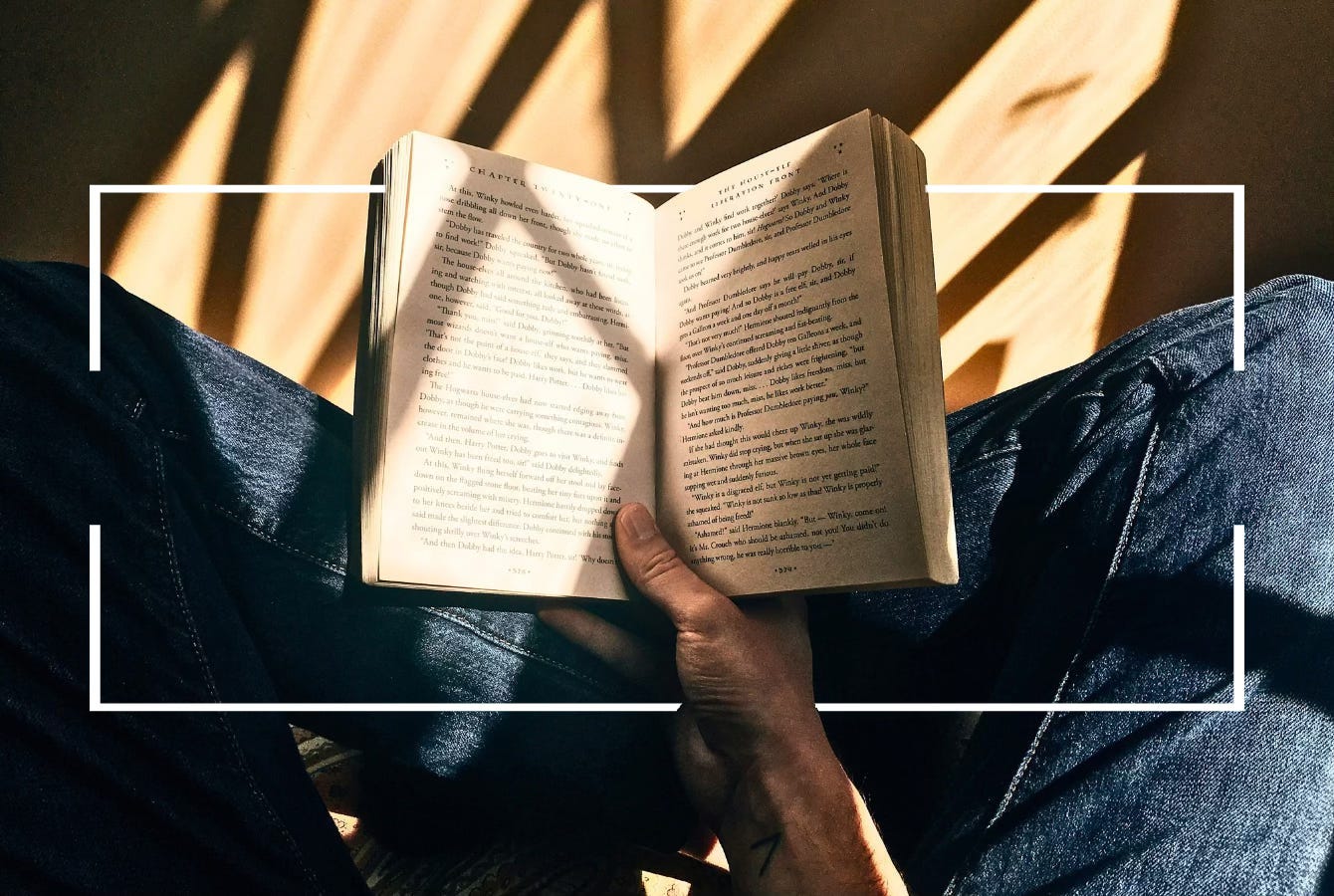

After the bland necessities of relieving my aching bladder and brushing my teeth — my zombie-stare fixed on the over-the-sink mirror — there’s a bubble of time and space in which I brew then sip my coffee and sit with a book. I often have specific reading earmarked for the bookends of the day; it’s almost always a novel, occasionally non-fiction if it has a strong enough narrative thrust. This early reading is the rev of the engine as I gear up my brain for the more attentive and deliberate work I’ll do later. For now, the feet go up, the book rests on my knees, and the world outside my reading is quiet.

After about an hour of this, I get off the sofa and go into my study. Here, the morning blooms into fruition as a time of work, of building something, of sweat and effort. A morning without work feels to me like “a dwindled dawn”, a simile appropriated from Emily Dickinson (although her diminished daybreak was caused by an absent companion rather than a Protestant work ethic). My construction tools are pen, paper, and computer. In The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), Christine de Pizan encourages me from six centuries ago to not “hesitate to mix the mortar well in your inkpot and set to on the masonry work with great strokes of your pen”.

This work depends, of course, on the prior and ongoing work of serious reading. Construction happens here too — the novel does its work, just as I do mine. Milan Kundera reminds us that the work of a novel, its “sole raison d’être”, is to “discover what only the novel can discover”. The novel is, in this sense, both the cartographer and the map itself. He puts it even more strongly when he tells us:

“A novel that does not discover a hitherto unknown segment of existence is immoral. Knowledge is the novel’s only morality.”

This is why morning reading is more intense than reading at other times. This is reading in which I’m consciously analytical, deliberately processing what I read. Pleasure here is an epiphenomenon, not the primary virtue. The narrative flow is resisted, and rather than being washed with joyful abandon along the current of plot, I paddle backwards to slow my movement and eddy around ideas, noticing everything I can about the nature of the water.

John Gregory Dunne thought that understanding is wrought from the act of writing:

“Clarity only comes when pen is in hand, or at the typewriter or the word processor, clarity about what we feel and what we think, how we love and how we mourn; the words on the page constitute the benediction, the declaration, the confession of the emotionally inarticulate.”

As Henrik Karlsson writes in a wonderful piece on his substack, “My thoughts are flighty and shapeless; they morph as I approach them. But when I type, it is as if I pin my thoughts to the table. I can examine them.” The same is true (though in subtly different ways) for the reader — but the reader’s clarity comes when a book (rather than the pen) is in hand. I often discover what I think and feel through the words of others more articulate than I am.

Reading this way for so long with such assiduous attention is thirsty work, so a mid-morning coffee — and some kind of snack — is demanded by a weary mind and hollowing stomach. Afterwards, with caffeine renewing my preparedness for the demands of deep reading, I return to my study and my book. I remain here in concentration until the internal alarm clock of a hungry stomach strikes again, this time insisting on a substantial lunch.

MIDDAY

Midday is a silly time, a frivolous pause in the day, and my favourite literary association is Mercutio’s quip, in Romeo and Juliet, telling the about-to-be-scandalised nurse that it’s midday. He euphemises it by saying:

“[T]he bawdy hand of the dial is now upon the prick of noon.”

Afternoon delight, indeed.

AFTERNOON

My afternoon reading is often decided by the vagaries of whim. The richness of the sunshine and the angle of shadow it casts behind the pine outside my window; a fleeting memory flitting into my mind from the nowhere space all thoughts and memories arise from and subside into; the languorous, lazy desire to be more leisurely in my reading — such overlapping character traits and happenstance conditions, all part of the palimpsest of personality, determine what I read next.

This kind of reading is also a form of travel. Books are a literary space through which we move. We journey through the psychic space of ideas and travel across continents when we read. Roald Dahl’s precocious Matilda leads the way here:

“The books transported her into new worlds and introduced her to amazing people who lived exciting lives. She went on olden-day sailing ships with Joseph Conrad. She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and to India with Rudyard Kipling. She travelled all over the world while sitting in her little room in an English village.”

This explorative spirit is given a fresh lift, like a hovering gull rising on a sudden breeze, by taking a walk with the book. This is a skill many don’t have or worry they won’t have, and the risk of discovering they’re right about this is a face met with a lamppost. To the extent that I have this skill, it’s a graceless, stalling talent that involves the mechanical switching of one’s eye from page to the world five feet ahead and back again without losing the flow of the sentence. Reading is slowed and the stroll is often little more than a toddler’s tentative steps in an adult body. Still, it’s worth the effort to have the dual pleasures of reading and walking outside, so I attempt it today.

The book in my hand transports my mind as I transport myself around my neighbourhood. Lawrence Durrell, in The Dark Labyrinth (1958), suggests that “paradoxically enough, travel was only a sort of metaphorical journey — an outward symbol of an inward march upon reality”. This accounts for the pleasing congruity between motion and mind experienced during walking-reading, in which physical movement matches the sense of boundless travel within one’s mind as I leap, page to page, from continent to continent, a period in the distant past to one in the far future.

Eventually, I turn back towards home, and I return also to young Matilda and her books. Dahl tells us that “Matilda’s strong young mind continued to grow, nurtured by the voices of all those authors who had sent their books out into the world like ships on the sea”. She, like every confused soul seeking solace in literature, knows that novels will teach her more. And not only do readers seek and find ideas in books, those ideas seek and find us. From a prison cell in Turkey, where he’d been sentenced to spend his life, Ahmet Altan wrote an essay called The Writer’s Paradox (2017). In it, he assures the world outside of his prison cell:

“Each eye that reads what I have written, each voice that repeats my name, holds my hand like a little cloud and flies me over the lowlands, the springs, the forests, the seas, the towns and their streets. They host me quietly in their houses, in their halls, in their rooms. I travel the whole world in a prison cell.”

When we journey through books, we carry their ideas new places too. Reading — I realise as I have before and will again at other times in my life — is not only a pleasure, it is a responsibility.

SUNSET

“Lamplight, wine and good conversation sealed in the margins of the day,” Lawrence Durrell writes in Bitter Lemons, “so that one slept at night with a sense of repletion, of plenitude ...”

I always enjoy the end of another day when sliding into bed with the satisfaction of earned exhaustion, nourished by reminders of the things that matter most. This isn’t falling into a slouched stupor on the sofa, watching Netflix as time slides by until the body is dragged to bed. It’s a thoughtfully prepared dinner; a glass of wine shared with loved ones; conversation that becomes debate, good-natured and intentional; the homecoming of a favourite book and bed. The sun sets as a backdrop, the lowering curtain on my day of reading.

In Bitter Lemons, Durrell describes the kind of person who’s made something of being fully who they are, people for whom “style was not only a literary imperative but an inherent method of approaching the world of books, roses, statues and landscapes”. Do not, we’re advised, fall haphazardly into saying whatever might fall out of one’s mouth; don’t merely express any and every opinion; read books, think about them, and express something of worth about your reading. The same goes for movies, art, gardening, exercise, raising children, or travel. Here are the friends Durrell describes during his evening entertainments:

“Freya Stark ... illustrated for us the wit and compassion of the true traveller — one, that is, who belongs to the world and the age; Sir Harry Luke ... who was fantastically erudite without ever being bookish, and whose whole life had been one of travel and adventure; Patrick Leigh Fermor and the Corn Goddess, who always arrive when I am on an island, unannounced and whose luggage has always been left at the airport (‘But we’ve brought the wine — the most important thing’).”

And later:

“In that warm light the faces of my friends lived and glowed, giving back in conversation the colours of the burning wood, borrowing the heat to repay it in the companionable innocence of unpremeditated talk.”

The final moments of the day arrive, a period of transition from day to night, waking to sleep, active to resting. Here, propped up with pillows against the headboard of my bed, I bookend the day with whatever I was reading when it began. This is the kind of reading in which there’s no resistance, no work to fight against the current, but the wilful submission to the narrative flow. I allow the story to do what it likes with me, to make me feel what it will without the intrusion of my mind and its otherwise constant analyses.

The stage is now set for sleep and dreams. Truthfully, I’m deeply uninterested in dreams. The rationalist in me itches at the lack of logical causality and the storyteller resents the lack of narrative causality. I side in this regard with Shakespeare’s Mercutio when he chides dreams as being “the children of an idle brain; / Begot of nothing but vain fantasy ...” Still, there’s something to be said for the quiet, unconscious work dreams do to shape the waking consciousness. As Anaïs Nin puts it:

“When I lie down to dream, it is not merely a dust flower born like a rose out of the desert sands and destroyed by a gust of wind. When I lie down to dream it is to plant the seed for the miracle and fulfilment.”

This is what I hope for as I put my book on the bedside table and turn off the lamp.

NIGHT

Sometimes sleep slips past me, sliding over the rest of the darkened world, subduing my wife so deeply in its soporific wash that she snores as if reality itself tears with her every snort and gasp. On these insomniac nights, if the fight to slip into slumber is lost and I begin to get irate, anxious about how difficult tomorrow’s going to be, I get up and go to the front room. A lamp goes on, my feet go up as I sprawl across the sofa, and I consider what I want to read.

Night reading is special. For people without any sleep complaints, it may never happen as an adult, but all life-long readers have cherished memories of reading at night as a child. I have many specific memories of doing this, but when I think about losing myself in a book through the dark hours, I conjure up a borrowed image of a child who is not me, sitting on a bed with the duvet over their head so they form a human-blanket tepee, a torch in hand, scanning the pages of a story. Where the image is from, I don’t know exactly, but it seems to be some culturally common archetype. Perhaps it comes from the third Harry Potter movie, which begins with the boy wizard in exactly this pose, practising spells under his blanket at night — although it seems more likely that the scene was shot in that way because of the shared imagery that pre-dates the movie.

There’s always something of childhood about reading at night, for me at least. It was a dark and stormy night — I always want it to be when I’m awake and no one else is, and I’m between reality and dreams, and magic might be real and so might monsters. On other nights, I’ve read Jekyll & Hyde by Stevenson, or The Fall of the House of Usher by Poe, or The Lost World by Conan Doyle, or the same title by Michael Crichton. Tonight, I read Frankenstein.

As I read, I allow myself to fantasise about writing my own novel about dinosaurs (there must be a new way of writing a literary adventure with extinct predators!) or bringing Victorian horror into the twenty-first century, a postmodern take on the penny dreadful perhaps. If the far-fetched fantasies of the nocturnal mystic are ever to survive the light of day, they must be tempered in the morning’s rationality. H. G. Wells endorsed the marriage of the Apollonian and Dionysian in The Time Machine (1895), writing that an idea might seem “plausible enough tonight, but wait until tomorrow. Wait for the common sense of the morning”.

The marriage of reason and madness might just be the formula for creativity. There’s an old saying (old, yet not quite as old as Nietzsche, to whom the aphorism is often misattributed): “They who dance are thought mad by those who hear not the music.” When the dreamer writes his novel or her short story, we’re made to hear the music of their madness. It wakes us to the beauty and truth they show us in their books. That awakening then causes us to dream, before we start another day and another fresh page, and we write something new.