Hi everyone,

The spooky season is upon us, and honestly it’s my favourite time of year. Halloween isn’t as large a part of the culture here in the UK as it is elsewhere, and I long for the kind of North American Halloween festivities I see in the holiday films I enjoy every Autumn, celebrations that seem to take over whole towns and last longer than just the day itself. The jack-o-lanterns and thick jumpers, the pumpkin pie and hot chocolate, long walks in the rain and the smells of autumn… All of these and a scary film at the end of the day is all I need to be happy in October.

I don’t have much to say here above the line, no updates or announcements, so I think I’ll get out of my own way and get straight into discussing some of the things I want to recommend from recent weeks.

Watching:

Anyone who’s spoken to me about what TV I’ve enjoyed over the last year knows in exhaustive detail how much I loved Mike Flanagan’s Midnight Mass. I enjoyed it so much I wrote this essay on it. It was so much more than I’d been expecting: as a series (I’m not as taken with serialised stories as most people I know); as something produced by Netflix (their very few remarkable gems are buried beneath an ever-growing pile of cinematic rubble); as the latest offering from Mike Flanagan, whose first series, The Haunting of Hill House, I was lukewarm on and whose follow-up, The Haunting of Bly Manor, was so abysmally dull that I couldn’t get past episode 3. And then Midnight Mass came along and spoke to something deep inside me, articulating things I’d not been able to articulate even to myself.

So when Netflix released Flanagan’s latest series, The Midnight Club (no relation to Midnight Mass), I wondered as much about what kind of quality we’d be getting as what the story itself would be. The short version is that there was enough to chew on thematically that next month’s essay will be on a subject raised in the show, and I had a lot of fun for most of its episodes, but it is bloated in places and frequently holds the viewer by the hand to make sure no subtext or metaphor gets overlooked. And it is very definitely a teen drama, which is no bad thing – teens deserve TV of their own, after all – and it may actually be quite a good thing.

A few years back, Evan Puschak of the Nerdwriter YouTube channel made a video-essay in which he looked at the craft of Alfonso Cuaron’s Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. (You can watch the video-essay here.) Noting the positive role the Harry Potter books had on a whole generation of readers, Puschak says of the adaptations, “I think their commitment to good cinematic work was potentially just as important for young people’s filmic education as J. K. Rowling’s accomplishments were for our literary upbringing.”

His essay has much to say about Cuaron’s directorial techniques and the ways they contribute to the film’s themes and emotional beats, but ultimately there is as much value in the very simple question so many of these techniques (such as the camera pushing “through” windows and even through a mirror) raise in the minds of younger viewers: “Wait – how did he do that?”

Movies such as The Prisoner of Azkaban and the Paddington films speak directly to children while showing them that movies can do and be so much more than thinly disguised advertisements for toys or mindless distractions. My hope is that The Midnight Club might do something similar for teens, who are so often shortchanged in the soap-opera crap served up to them in things like the Twilight franchise or the emotionally flattened and creatively hollow MCU movies. Maybe it can show them that their minds don’t have to be switched off to have a good time.

Reading:

Many things have been lost to us in the vanishing of physical media, and one such lost treasure is the Making Of featurette found on DVDs and Blu Rays, and which once upon a time came at the end of VHS tapes after the credits had rolled. Before Blu Ray and DVD began their losing battle against streaming, a previous incarnation of the Making Of featurette had already died out: the official Making Of book. Many of my Saturday morning trips to the public library as a child landed me with a haul of favourite books about the movie magic of films such as Independence Day, and there was even a book on Jim Henson’s best movies. (I hadn’t, and still haven’t, seen The Storyteller, but the photographs of the boy-hedgehog hybrid still haunt me.)

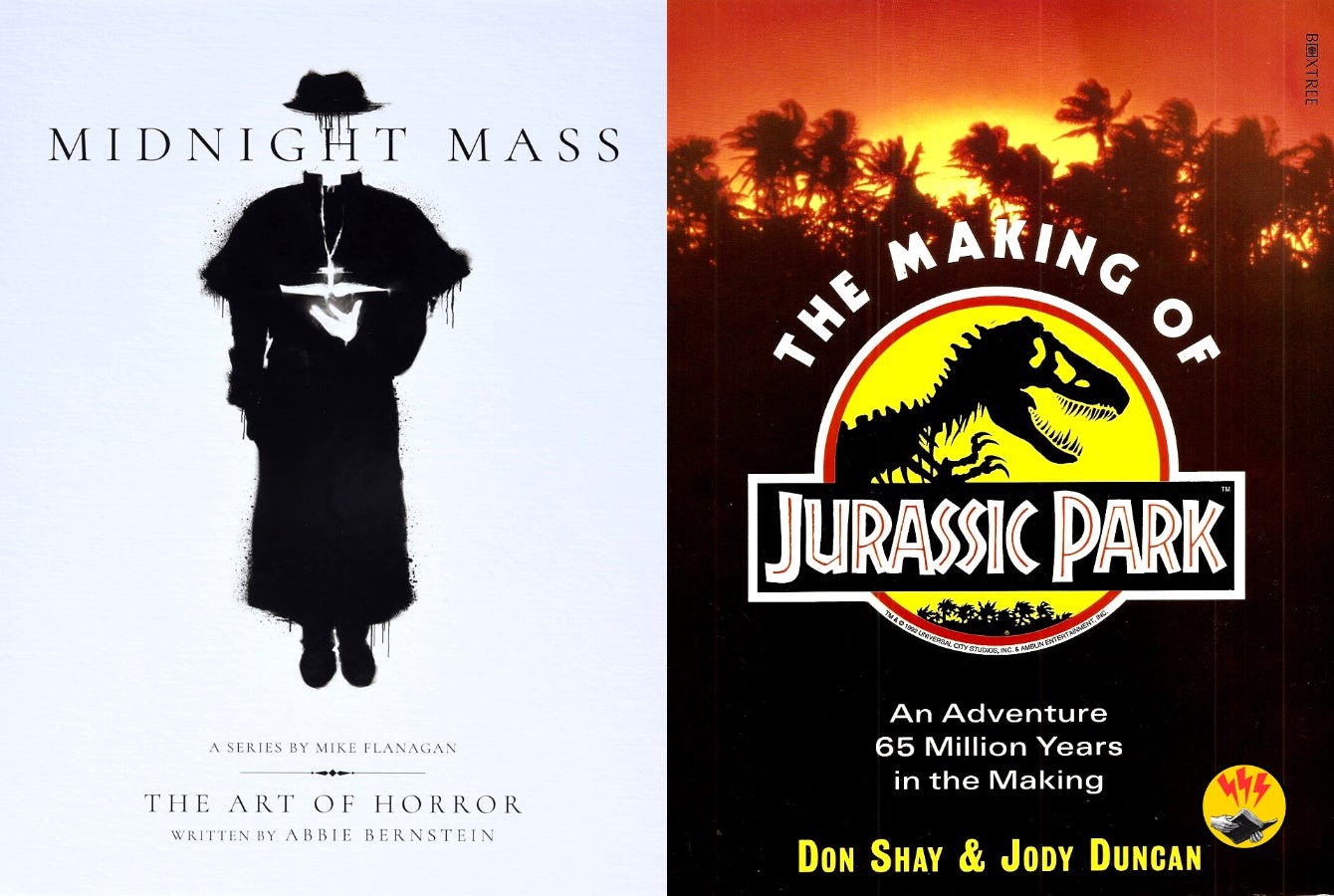

I’ve been rediscovering these literary-cinematic joys by reading a bunch of Making Of books. Top of my stack (and not at all surprising given what I’ve written above) is the official companion book to Mike Flanagan’s Midnight Mass. I’ve been reading all about the seed of this series as a novel Flanagan began and abandoned years ago, how he convinced Netflix to take on such a strange project, and the ins and outs of set design, costumes, themes, and all the other elements that make the world of the series so authentic. In its own way, it’s reminding me of a specific kind of magic that movies made me believe in when I was young.

I’ve also been reading the official companion books to Jurassic Park and Jurassic Park: The Lost World. The first comes complete with the storyboards used in the production of the film, a particularly literary treat that works well on the page and would work less well as part of a DVD feature. I must have always assumed that such books were labours of love by fans of the films, and no doubt some are, but the introduction to the book on Jurassic Park pulls back the curtain to reveal that Universal Pictures hired the two writers of this book and granted them access to actors, screenwriters, and Spielberg himself. I can’t imagine many studios today believing there’s enough of a market for a book that they would hire writers to put one out. Or maybe I’m being too cynical. If you have any recommendations for book tie-ins to contemporary movies, let me know.

Listening:

The latest (at the time of writing) episode of Andrew Sullivan’s podcast, The Dishcast, was titled "Richard Reeves On Struggling Men And Boys". In it, Sullivan had a wonderful yet bracing conversation with Reeves, who’s written a book called Of Boys and Men. The book tackles the various ways boys and men (whom they dub, playfully though not without good reason, “the weaker sex”) are falling behind in Western societies.

The book isn’t by any means an anti-feminist screed about the ways (as imagined by the far-right) that women oppress men; rather, it is a kind-hearted, thoughtful look at the ways men have failed to keep up as women have enjoyed the hard-earned and well-deserved progress they have made over the last half-century. As Reeves writes in the book:

“We can hold two thoughts in our head at once. We can be passionate about women’s rights and compassionate toward vulnerable boys and men.”

Reeves’ book and the Dishcast episode are warnings to society that unless we find positive ways to define and encourage masculinity, all our talk of what it means to be a man will be relegated to the chastising talk of toxic masculinity (a sort of gendered original sin in which a man can do know good except try to be more feminine) or an embrace of regressive, caveman-like brutishness.

Reeves shared a few statistics that shocked me and I think should shock all of us: Of the children whose parents separate, one-third of those kids will never see their father again. Another one-third will see him once a month or less.1 Let that sink in: 1 out of 3 kids will never see their father again after their parents divorce, and 1 out of 3 will see him once a month or less. This is a staggering blow to the stability of those children, as well as a huge impact on what kind of male role model they will have growing up.

Part of this problem must be laid at the door of court systems that reflexively prioritise the maternal relationship in custody trials, but I’m convinced that a far greater part of it is accounted for by the shirking of parental responsibility that comes with the indefinitely prolonged immaturity of our infantilised society. For a culture so obsessed with youth, we are remarkably cavalier with our young.

Not the happiest of notes to end on, but important things to consider. Anyway, thanks for reading, and happy Halloween!

Matthew

These statistics come out of the US, but similar studies reveal little difference in the UK. I would wager this is a Western problem generally with caveats for specific countries, rather than the US and UK being outliers in the Western world – but I’ll have to research the numbers to know for sure.