Milan Kundera: How Novels Defy Tyranny

On the role of art in defending all that we value.

Welcome to “Words of Wisdom”, a series that zooms in on a passage of writing — an essay, a chapter, a speech — from a great thinker on a specific topic.

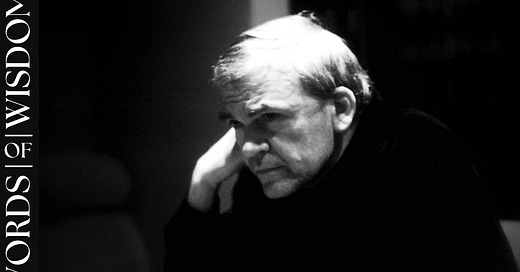

Today, Milan Kundera: a Czech-French novelist whose profound sense of humour took seriously the absurdities and contradictions of life. His last book before his death in 2023 was The Festival of Insignificance, a short and deeply ironic novella that confuses and inspires me in equal measure. Here, we’ll look at an essay from The Art of the Novel.

“The person who is certain, and who claims divine warrant for his certainty, belongs now to the infancy of our species.”

~ Christopher Hitchens1

New Atheism was very good — or at least always entertaining — on the absurdities of religious certitude, but it struggled with the kind of faith that struggled with itself. It’s not as easy, nor as entertaining, to mock the sincerity of people who confess, “I believe, but I don’t know for sure.”

While the closed-minded of both sides argue with each other, those in the middle get on with the task of finding ways to work together, of holding on to the light of faith while mindful not to be blinded by it. This is what Cardinal Lawrence (in Edward Berger’s Conclave2) is thinking of when he delivers this speech to his fellow faithful:

“St Paul said, ‘Be subject to one another out of reverence for Christ.’ To work together, to grow together, we must be tolerant — no one person or faction seeking to dominate another. And speaking to the Ephesians, who were of course a mixture of Jews and gentiles, Paul reminds us that God’s gift to the church is its variety. It is this variety, this diversity of people and views, which gives our church its strength.”

This is fairly standard-issue kumbaya ecumenism, the kind that helps get a film eight Oscar nominations and a win for Best Adapted Screenplay. (The film is also entertaining and elegantly shot, if somewhat silly and deflated by a fatuous ending.) But our cardinal swerves away from the feel-goods to caution his peers against a mindset that might undo all of this tolerance:

“Over the course of many years in the service of our Mother the Church, let me tell you, there is one sin which I have come to fear above all others: certainty. Certainty is the great enemy of unity. Certainty is the deadly enemy of tolerance. Even Christ was not certain at the end. ‘Dio mio, Dio mio, perché mi hai abbandonato?’ he cried out in his agony at the ninth hour on the cross.”

Certainty, argues the cardinal, is antithetical to those qualities of the Catholic Church (and, I’d argue, many other faiths) that are often overshadowed by unquestioning and narrow dogmatism. Cardinal Lawrence then says:

“Our faith is a living thing precisely because it walks hand-in-hand with doubt. If there was only certainty and no doubt, there would be no mystery and, therefore, no need for faith.”

This sense of faith as existing at the intersection between mystery and knowing, of containing contradiction even while being blown open by it, is something very like what Milan Kundera says separates literature from totalitarianism. In The Art of the Novel,3 Kundera celebrates the ontological distinction between the two, writing that “Totalitarian Truth excludes relativity, doubt, questioning; it can never accommodate what I would call the spirit of the novel”.

The Art of the Novel closes with Kundera’s acceptance speech for the Jerusalem Prize for Literature in 1985. In it, he suggests that the novel is a route out of the biases of an author and, therefore, a method of defying ideology:

“When Tolstoy sketched the first draft of Anna Karenina, Anna was a most unsympathetic woman, and her tragic end was entirely justified. The final version of the novel is very different, but I do not believe that Tolstoy had revised his moral ideas in the meantime; I would say, rather, that in the course of writing, he was listening to another voice than that of his personal moral conviction. He was listening to what I would like to call the wisdom of the novel. Every true novelist listens for that suprapersonal wisdom, which explains why great novels are always a little more intelligent than their authors.”

Kundera then asks what that wisdom of the novel might be, and poses a cryptic answer in the paraphrasing of a Jewish proverb: “Man thinks, God laughs.” Why, you might wonder, does God laugh when humans think? Kundera answers:

“Because man thinks and the truth escapes him. Because the more men think, the more one man’s thought diverges from another’s. And finally, because man is never what he thinks he is.”

The truth of this, Kundera argues, is revealed in the first modern novel, Don Quixote, whose protagonist thinks and the truth of reality slips away from him — he comes to believe ridiculous things about himself, his situation, and the world he moves through. Watching this absurdist comedy unfold, God can only laugh. The comedy is in the error; the tragedy, however, is in Quixote’s certainty, in his absolute and misguided conviction that what he erroneously believes about reality is in fact reality.

A novelist who thinks this way can always be discovered in the narrowness of their novel’s worldview and its lack of novelistic morality, which Kundera says is specifically to discover some “hitherto unknown segment of existence”. Just as an explorer fails if he never discovers unmapped terrain, a novel fails if it simply re-treads what the novelist assumes to be true. In describing how a novel escapes the restrictions of its author, Kundera brings up his favourite eighteenth century novel:

“Of all that period’s novels, it is Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy I love best. A curious novel. Sterne starts it by describing the night when Tristram was conceived, but he has barely begun to talk about that when another idea suddenly attracts him, and by free association that idea spurs him to some other thought, then a further anecdote, with one digression leading to another — and Tristram, the book’s hero, is forgotten for a good hundred pages.”

In describing Tristram Shandy as “a curious novel”, Kundera is playing with the duality of the adjective — the novel is both curious in being unusual, and curious in wandering from one idea to another. The book’s hero is lost for some time amid the exploration of ideas, and when the novel eventually comes back to Tristram, our understanding of the character has changed. This capacity for a novel to get away from its creator, to resist the dictates of the author’s ideology, is the laughter of God.

This is another way of thinking about the failed novel or novelist: that it or he has failed to hear God’s laughter. They are what François Rabelais called an agélast: “a man who does not laugh, who has no sense of humour.” Kundera explains why there can be no understanding between the true novelist and the agélast:

“Never having heard God’s laughter, the agélasts are convinced that the truth is obvious, that all men necessarily think the same thing, and that they themselves are exactly what they think they are.4 But it is precisely in losing the certainty of truth and the unanimous agreement of others that man becomes an individual. The novel is the imaginary paradise of individuals. It is the territory where no one possesses the truth, neither Anna nor Karenin, but where everybody has the right to be understood, both Anna and Karenin.”

It’s in the affirmation of the individual that the novel stands against totalitarianism, which attempts to negate the individual by subordinating her to the supremacy of the group, the ideology, or the tyrant (who can, in such systems, be the only individual permitted). And in its celebration of pluralism and transcending absolutes, the novel stands against the tyrannies of certainty. Here, Kundera opens the novels of Gustave Flaubert to parse wisdom from their pages:

“Of course, even before Flaubert, people knew stupidity existed, but they understood it somewhat differently: it was considered a simple absence of knowledge, a defect correctable by education. In Flaubert’s novels, stupidity is an inseparable dimension of human existence. [...] But the most shocking, the most scandalous thing about Flaubert’s vision of stupidity is this: Stupidity does not give way to science, technology, modernity, progress; on the contrary, it progresses right along with progress!

With a wicked passion, Flaubert used to collect the stereotyped formulations that people around him enunciated in order to seem intelligent and up-to-date. He put them into a celebrated Dictionnaire des idées reçues. We can use this title to declare: Modern stupidity means not ignorance but the nonthought of received ideas.”

Novelist Martin Amis called the clichéd phrases that perpetuate stupidity “herd words”. It’s this self-subscribed program of repeating other people’s bad ideas, through received language, that fertilises the ground out of which certainty grows. Certainty rarely survives sincere, intelligent scrutiny; the “nonthought of received ideas” is what certainty requires to perpetuate itself.

It’s fitting that we’ve arrived at the concept of the “dead words” that convey zombie ideas (dead but kept animated as if alive), given that we left Conclave with Cardinal Lawrence claiming that it’s a relationship with doubt that makes his faith “a living thing”. Faith and fiction of the most vital kinds share something equally essential: both are bulwarks against certainty, which is antithetical to life.

Kundera closes by noting that the agélasts and the nonthought of received ideas are one and the same — they are the “enemy of art born as the echo of God’s laughter”. This art and the faith that Cardinal Lawrence champions must be defended against certainty, because they create “the fascinating imaginative realm where no one owns the truth and everyone has the right to be understood”.

God Is Not Great, Christopher Hitchens (2007)

Conclave, Edward Berger (2024)

The Art of the Novel, Milan Kundera; trans. Linda Asher (1968; 1988)

In this, Kundera prefigures a line from Christopher Hitchens that I’m reminded of every time I meet a person with no sense of irony: “The literal mind is baffled by the ironic one, demanding explanations that only intensify the joke.”

Matthew, I appreciate these insights. I have only read one of Kundera's books, "The Unbearable Lightness of Being," but I am interested in exploring more of his work. My wife and I watched Conclave this past weekend. We thought it was well done and enjoyed it until the rather silly ending which kind of spoiled it for us. However, overall the movie was great.

As a reader, I value works that defy my expectations when the author goes beyond themselves to write something that transcends their experience. It is this foray into the imaginative realm that inspires me and lifts me up.